Cultivating cultural roots in cities: A deep dive into the inclusion of cultural elements in urban design

The planning industry is profoundly changing its design logic as it evolves from "rapid urbanisation" to "refined urbanisation." As standardised road networks and modular functional zoning lead to homogenised urban landscapes, the creative integration of cultural elements has become key to shaping a city’s unique vitality. Drawing on recent case studies, this Insight Paper by Urban Planner and Designer Chen Sen explores how cultural elements can transcend superficial symbolism and become the structural DNA of urban design.

I. Natural elements as cultural components

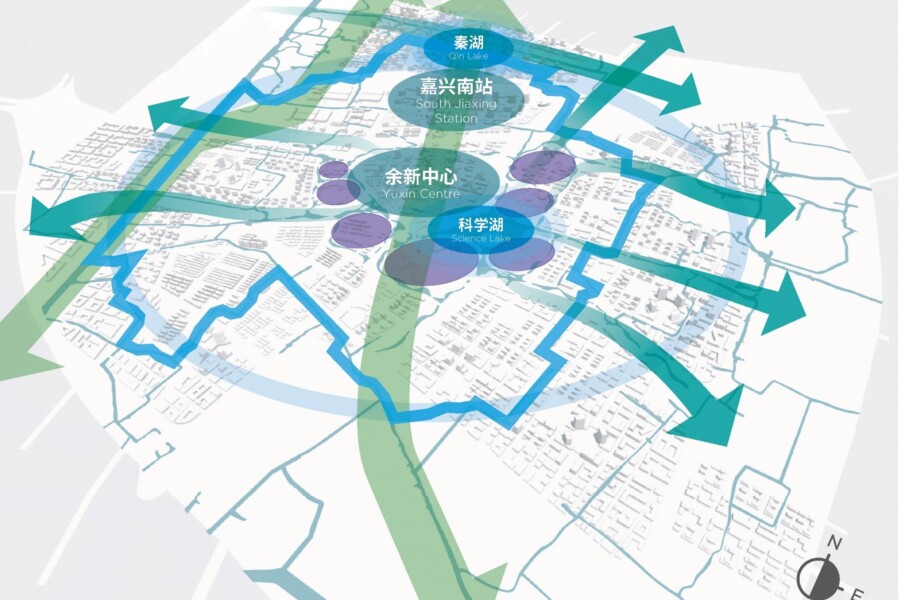

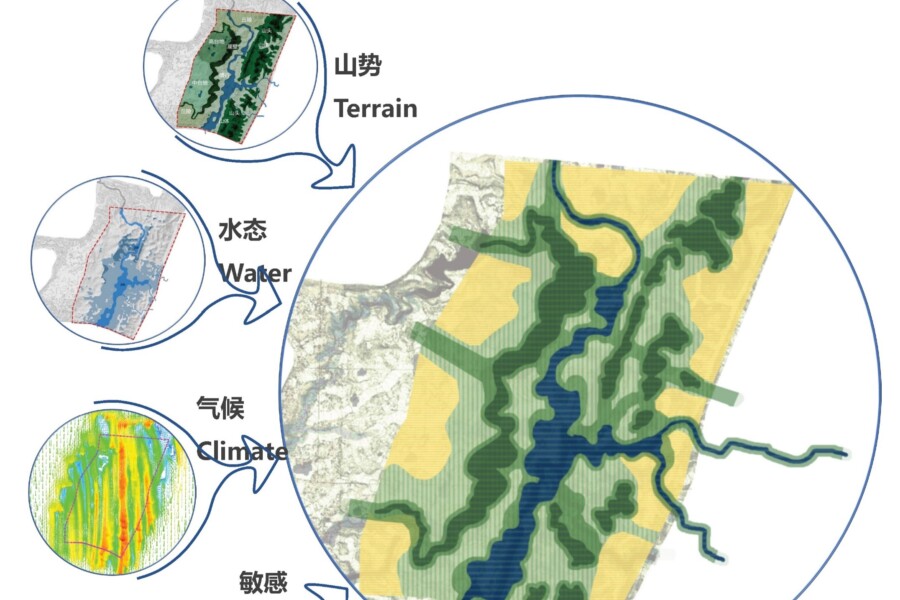

In designing the concept for Jiaxing High-Speed Rail New City, we moved away from the traditional Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) model that prioritises efficiency above all else. We discovered that the “nine waters converging” pattern represents the city’s true spatial logic. By topologically restructuring the water network alongside the rail transit hub, we developed a double helix system of “water veins + tracks”: the rapid transit core runs along the water branches. At the same time, the riverside areas serve as capillaries for the slower-moving urban fabric. This design continues the legacy of Jiangnan’s water-based urban planning while modernising flood management through a water-level regulation system. The project successfully demonstrated the cultural translation value of natural elements.

City structure of Jiaxing City -Nine waters converging | Planned city structure of Jiaxing south station area

II. Storytelling with locally familiar elements

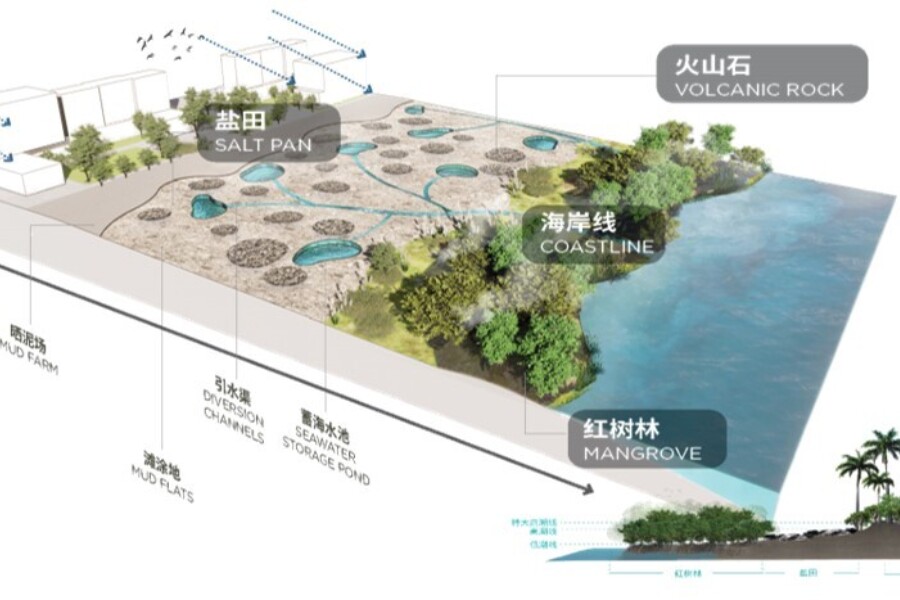

For the design of Hainan Yangpu Riverside, we translated local cultural symbols into immersive spatial narratives, weaving regional memory into the physical fabric of the city:

- Form translation: Yangpu’s rich volcanic stone resources are natural and cultural symbols. We interpreted their textures and materials in the architectural language, integrating buildings with the landscape and enhancing regional identity.

- Spatial translation: Yangpu’s historical salt fields informed the grid-like organisation of public spaces, embedding a strong sense of place in the layout.

- Behavioural translation: The labour scenes of the salt fields were abstracted into interactive public elements. Landscape design and artistic installations transformed the salt-making process into a cultural experience.

These translations helped local cultural symbols move beyond visual representation, becoming deeply experiential and narrative-rich urban design elements.

III. Focusing on the underlying logic of cultural phenomena

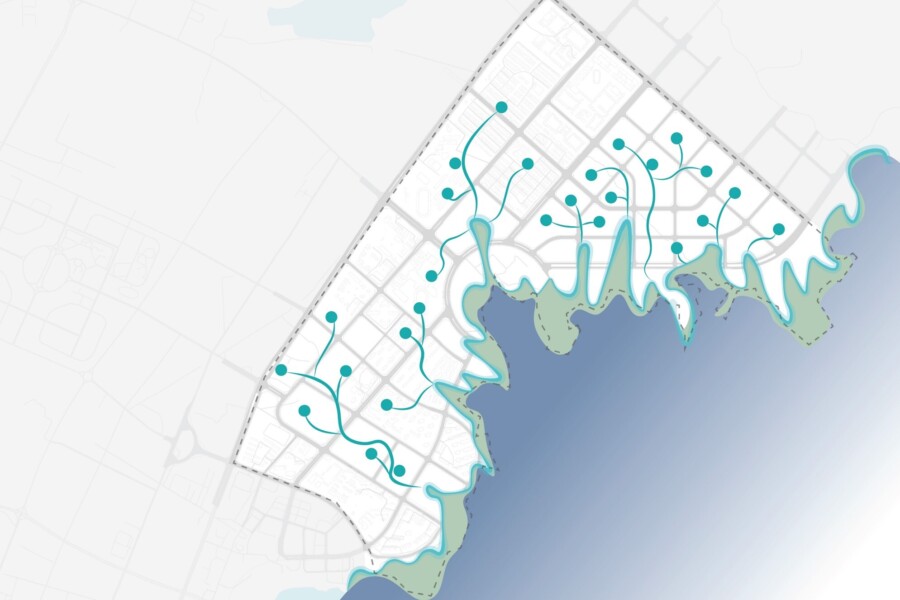

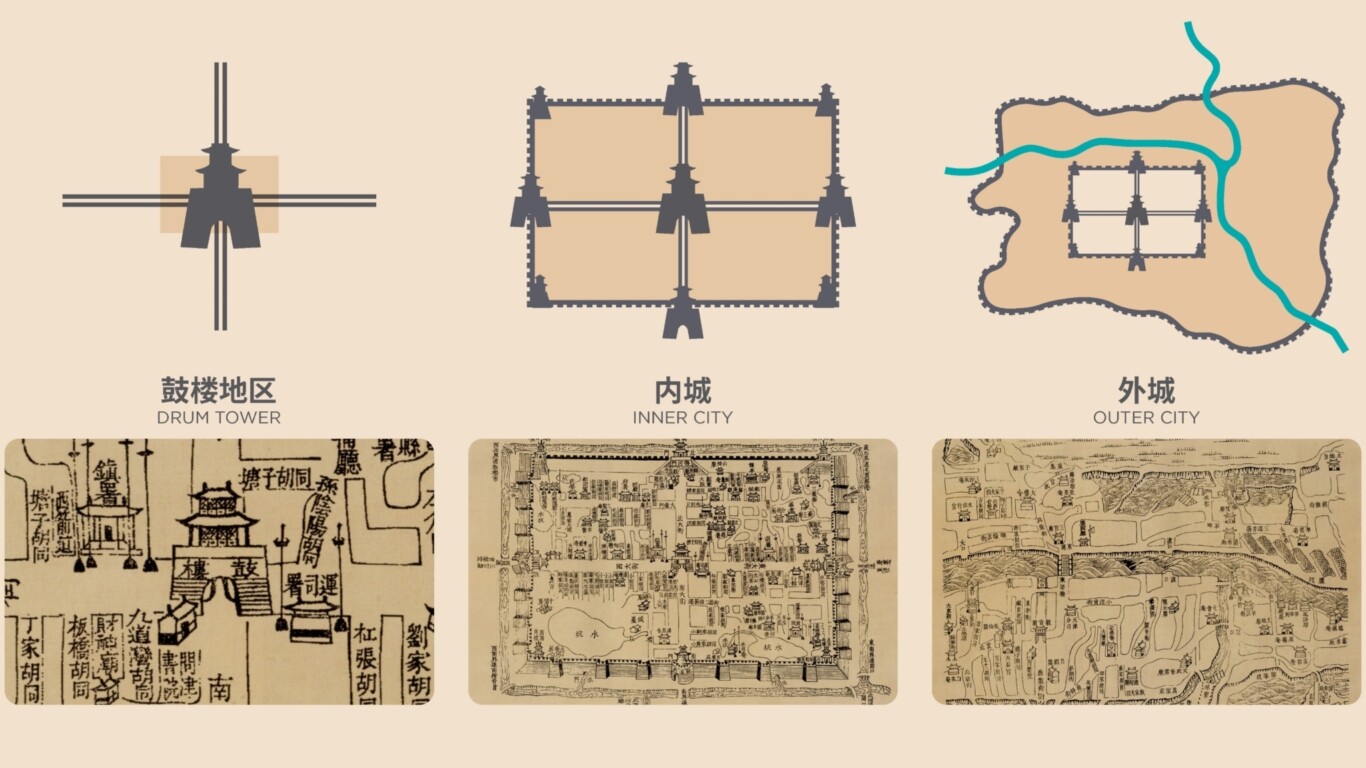

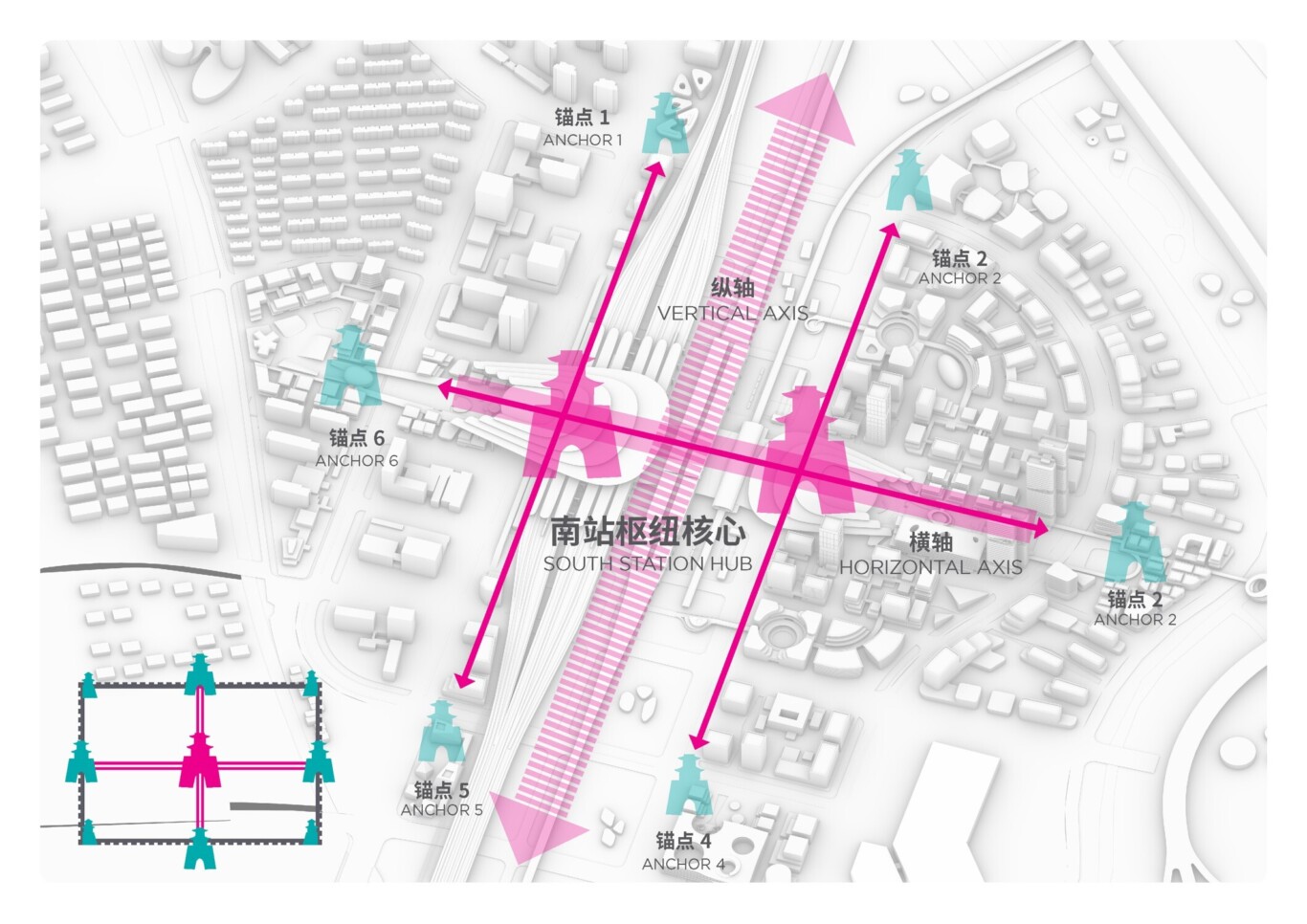

The design for Tianjin South Station explored the deep logic of cultural inheritance. Rather than simply referencing traditional forms, we reimagined the ancient city's “dual-city structure” while applying the governance principle of “government-led + market-driven” development.

- The inner city adopted a TOD-controlled framework, while the outer city developed as a series of flexible zones along the river.

- We introduced “plot gene coding” rules, enabling developers to adjust floor area and function ratios parametrically.

- We preserved the blurred edges of traditional alleys and used them to restructure interaction networks within modern industrial parks through “grey space chains.”

This algorithmic reinterpretation of traditional urban planning converted historic wisdom into quantifiable design tools, creating a replicable model for station-city integration.

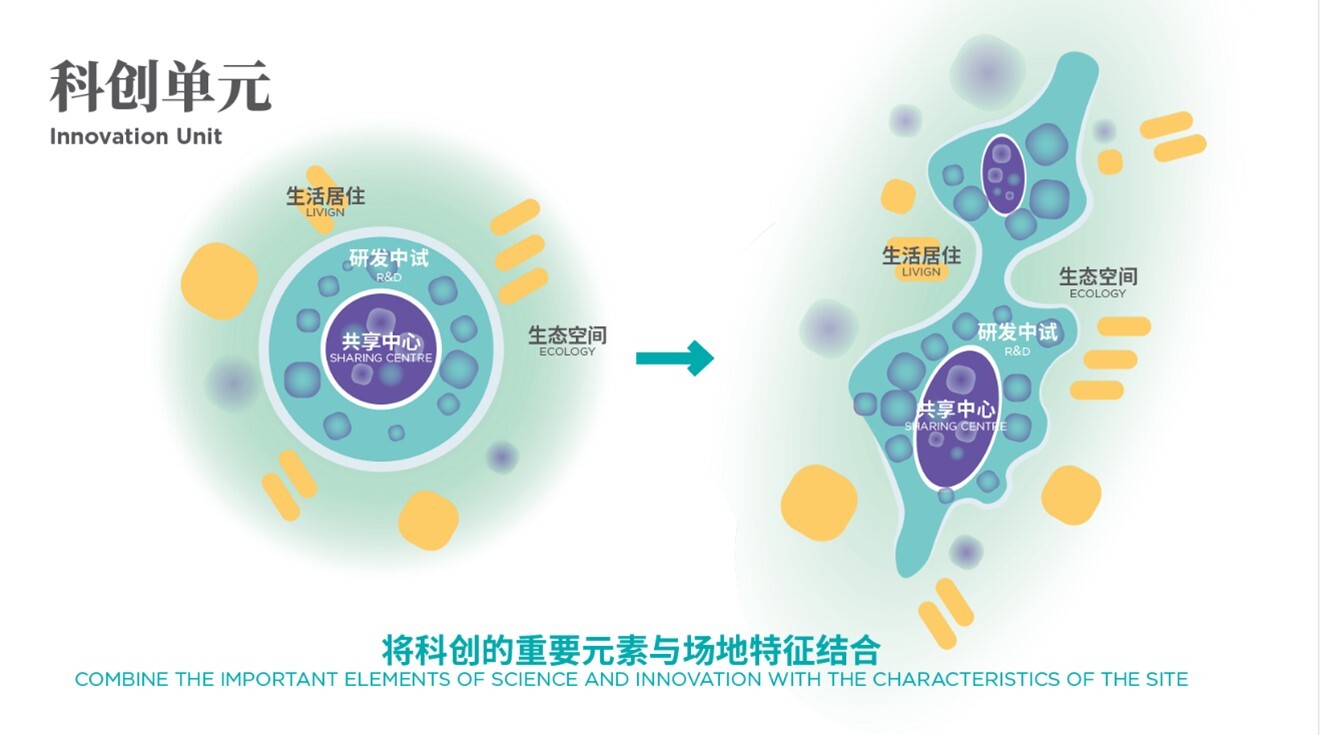

IV. Using culture as a catalyst for innovation

In Chongqing Liangjiang Innovation Park, we explored how cultural understanding can drive innovation in site-specific design. Faced with the city’s unique mountainous terrain, we decoded cultural principles to adapt the science park typology:

- We analysed Chongqing’s “three-dimensional living" including humidity-responsive ventilation, elevation-based social organisation, and cliffside construction methods.

- We developed a “topography–industry—space” mapping model: we situate algorithm labs on cliffs for views, bio-labs in valleys for natural cooling, and vertical communities of terraced apartments.

- We introduced a “cloud and mist corridor”, a smart ecological system inspired by traditional stilt houses' ventilation strategies.

This creative transformation of cultural knowledge led to the development of custom design standards tailored to mountainous innovation hubs.

Conclusion

The ultimate goal of urban design is to foster a self-sustaining cultural ecosystem—one that evolves while preserving each city’s unique cultural chromosomes in its spatial gene bank. As designers, we are responsible for placing and embracing cultural consciousness in the next phase of urbanisation.