How to breathe life back into our high streets

Senior architect Jonathan Jones discusses some of the design opportunities and challenges with repurposing redundant shopping spaces – essential for bringing vibrancy back to our town centres.

Everyone is familiar with the story. Whether it’s high streets, shopping centres or department stores, there’s a lot of redundant space. This overprovision of retail is out of step with our current needs and habits.

According to the Local Data Company (LDC), ‘Vacancy rates serve as an essential barometer for retail health… Retail vacancy rates remain at a record high, but this figure looks set to decline as more units are taken off the market for repurposing.’ (1)

How has this come about?

Online shopping is convenient and low-cost. It is drawing physical retail away from the high street, and people’s habits are changing – particularly the younger demographic. People are also moving out of town centres and using them less, in part due to poor planning decisions.

Tenants are approaching an EPC cliff edge. ‘Energy performance certificates (EPC) regulations are urgently bringing into focus the need to improve the energy efficiency of all commercial buildings. A staggering 83% of retail stock nationally will need to be improved by 2030.’ (2)

The overhead cost of maintaining physical retail spaces simply prices some retailers out of the shop front.

Traditional retail spaces can lack reactivity. A physical store can’t compete with online environments in this sense and can quickly stagnate without reinvention and investment.

Our retail sites

When considering an opportunity, one of the first things to consider is the site. How well or how poorly has the building responded to its context? One of the biggest failings of retail developments is the ‘spaceship landing’ effect, ignoring local context, historic streets and the scale of city blocks, for example. After hours, can people navigate through it or do they have to go around? And how safe does that feel?

It is worth recognising that we have a range of types of shopping space across the UK and each comes with a unique set of characteristics.

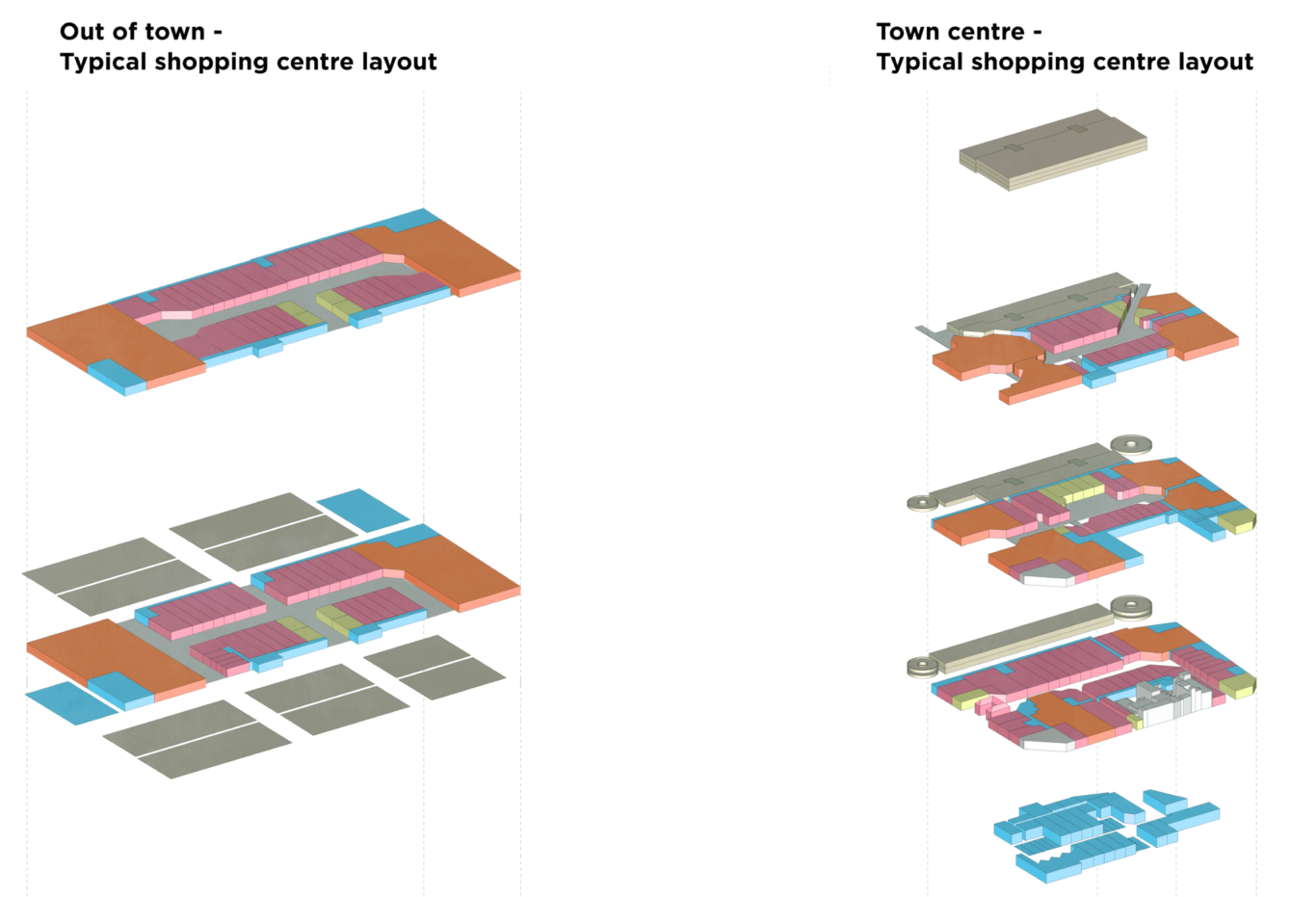

We have a huge number of post-war modernist shopping precincts that have evolved over time, taking influence from the North American retail malls - enclosed, air-conditioned, fairly sterile environments. These are car-oriented models, with surrounding surface car parks, focused on how you drive there rather than how you access as a pedestrian or via public transport.

When you take these models and try and shoehorn them into a town centre, the layout and building diagram can become compromised. It’s a lot harder as a pedestrian to understand how you might get from A to B and the area becomes impermeable. These inward-looking spaces have to have a servicing or back-of-house element which can lead to service corridors and blank facades that create a very unwelcoming environment with poor surveillance - undesirable spaces that make people feel unsafe.

This formulaic inward-looking approach, with multiple brands, has led to what some people call ‘clone town syndrome’ – if you were to drop into one of these places, it would be hard to tell if you were two miles down the road, or 100 miles away.

There is obviously an opportunity to open these spaces up and create a meaningful connection to what is happening beyond. To create a sense of place.

Contemporary department stores can similarly feel out of place, a big box with no windows, taking up a sizeable chunk of our high streets. More traditional department stores often have significant heritage and prominence. So, there can be amazing character and dramatic interiors, but there are design challenges when it comes to manipulating or retrofitting this type of space. For example, large floor-to-floor heights, requirements for means of escape, and trying to retrofit contemporary regulations and standards such as limiting operational carbon or fabric fire protection.

The challenge for landlords

Landlords need to be proactive or face the daunting prospect of becoming irrelevant. Rather than be pessimistic, there’s an opportunity to react quickly and reposition. We work with clients to explore alternative solutions.

What potential schemes could work within their sites and the assets that they have?

More than retail

To address the fact that there is too much retail space we need to consolidate, compress and diversify.

Mono-use retail is too limiting. We need to go back to the more traditional concept of a high street, with a real variety of independents and types of offers. When you think about the traditional high street, people were living above shopfronts and there were also multiple workplaces and hospitality uses. When you start integrating this mix of functions, everything becomes richer.

In the first instance, we can identify uses to occupy that space and start to reanimate streets. What are those activators in our town centres? How can we create an ‘active edge’ on a retail scheme? An active edge is an illuminated space that provides a spill out of activity on a street, making it feel safe and creating a vibrant and inviting area. It creates overlooking and animation.

What’s working?

According to the Office of National Statistics, as of September 2022, internet sales only made up 25.3% of retail sales, and although this number is increasing, retail will continue to be a significant element on our high streets.(3) As part of consolidating the retail offer, we must understand how to introduce complementary uses and what they will bring as a benefit.

Chapman Taylor’s knowledge and research about design can be very useful for clients who are considering introducing a mix of uses into their schemes.

It's worth building on what is working and what are people responding to. For example, an established food culture within the local community can be emphasised and built into a place's identity.

Through the pandemic, there's been a greater understanding of what is local to me, the concept of hyperlocal - what amenities are within a 15-minute walk from my house. We’re seeing mini-hubs popping up but there needs to be a balanced mix between your local hub and major hubs and how they interplay. Figures from the LDC are showing the growth of independent retailers, signifying a move towards the traditional high street:

‘Independents continue to thrive in the GB market, outperforming national chains in every classification. Independent convenience occupiers saw the biggest percentage increase in H1 2022, with a rise of 1.6%. Localisation has been a core theme in our reports since the onset of the pandemic; with restrictions limiting mobility, much of the population began to shop locally and more frequently. This trend has persisted, to the benefit of local convenience outlets, although it will be tested as price becomes ever more important.’ (4)

Uses to consider:

The first thing to consider, is what are the schemes that are working well? What examples do we have of schemes that have been designed with a more sensitive consideration of place?

Trinity Kitchen is an archetype for bringing in a casual, street food offer to a shopping centre. It’s been hugely successful. Encouraging shoppers to extend their stay but also acting as a destination in its own right. Adding F&B outlets is an easy first step – it’s about supplying an experience, something that younger generations with different priorities will appreciate.

Leisure uses are a useful tool in your arsenal because they have quite similar requirements to big box retail. For example, Gravity in Wandsworth brings in a competitive socialising experience and is able to make use of large department store floor plates. It’s also able to use some of those awkward spaces like basement areas where they have a Go Kart track.

Uses like these are incredibly important when trying to bring people back into centres, to create urban living environments that are rich and vibrant. When considering residential, this vibrancy is essential but it’s also about improving quality. Having access to really good, safe, outdoor spaces, like in Castle Park View in Bristol, or Kampus in Manchester. It’s a good way to fight the suburban sprawl and create sustainable communities in our centres again. There’s a housing crisis and empty space in our centres. There is an obvious solution there!

Incorporate a diverse range of uses like workplaces and hospitality elements. The key consideration is, can we re-purpose existing buildings or new-build? How does the modular grid line up with the existing facade of a retail floor-to-floor which is very different from residential or hospitality floor-to-floor? We can also consider education and higher education uses, and ‘meanwhile’ tenants that can act as a test bed, allowing a continuity of activity whilst more long-term leasing strategies are developed. Bringing in a mix of uses extends the hours of activity and can animate a scheme and make it feel safe and neighbourly.

Considering the introduction of green spaces can be incredibly positive, too, not just from an environmental perspective. We’re starting to see some schemes that are quite bold – such as converting redundant space into parks and other green social spaces. And with that, the value of adjacent spaces increases and it can start to be a bit of a catalyst. But this is longer-term thinking and requires support from Local Authorities in order to take some of the risk away from Developers.

Balancing short-term needs with a long-term vision

Understanding value and viability is essential.

No matter the type of space that you're looking at, there's always a solution.

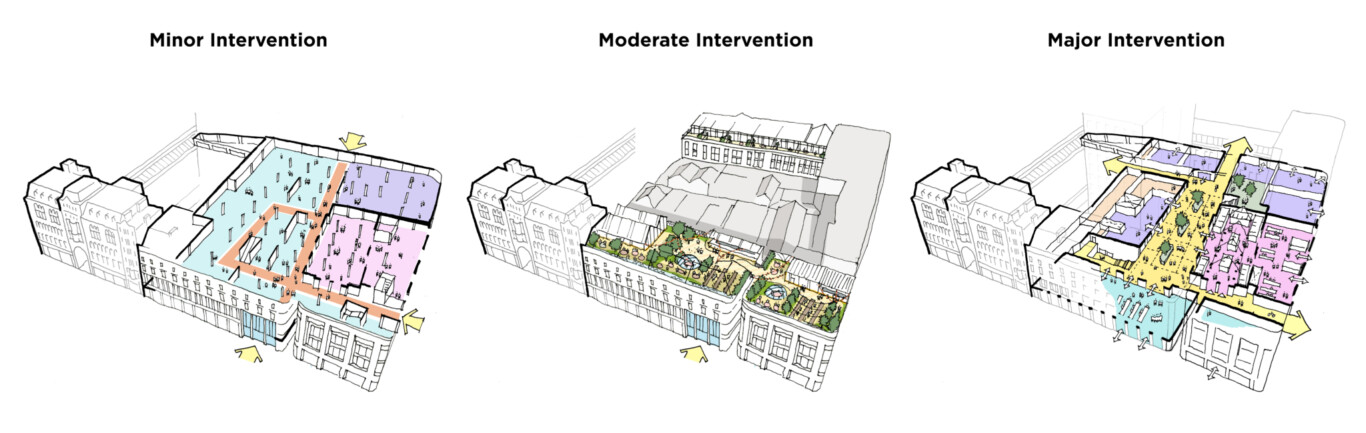

The easiest transition is to think about uses that can immediately be incorporated to activate those redundant spaces. It's easy to do the small-scale interventions, bringing in new tenants to plug the gaps, but this short-term view can obscure the potential for long-term development that might be a bigger financial risk, but of greater overall benefit.

It’s also important to have a long-term vision for the future and how might you make incremental steps towards that.

The value of an asset can rise and fall. On top of this, market changes in construction costs can render a potential scheme untenable. For larger-scale opportunities, the development process can take many years. To try and predict with certainty that a use type is going to be relevant or on the pulse in a decade's time is a really hard thing to forecast.

It’s important to have a macro view. You need to understand what your neighbours are doing. What the footfall in that whole area is predicted to be and how it's going to be used in general. Local authority support is hugely important with fragmented ownership across UK town centres. More Compulsory Purchase Orders and more government funding will go a long way to turn an exciting opportunity into an opportunity, and to allow a vision to become reality.

Summary

It is essential to bring vibrancy back to our town centres. At Chapman Taylor, we work with a vast range of clients to help them consider solutions to create commercially successful spaces that will also enhance the lives of the people that interact and use them.

From how you might start to introduce a mix of tenants and uses, to improving dwell spaces and entrances and creating an active edge; to considerations about how to build a centre identity and a more meaningful mix of uses, creating a masterplan with an eye on that longer-term vision so you’re not investing in a space that might need to be rethought in order to ‘unlock’ a later phase. At all times it’s important to understand what the local need is and to start creating meaningful connections with the city context. And, in so doing, to create a real sense of place.

(1) www.localdatacompany.com Retail and Leisure Trends Report 2021

(2) Re: Imagining Retail, Issue 3, How will retail places go green? Savills, 2022

(3) The Office for National Statisticswww.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/retailindustry/timeseries/j4mc/drsi

(4) http://www.localdatacompany.co... H1 2022 retail and leisure trends analysis