Restoring authenticity to our local high streets

As the era of big-name-retail domination of our high streets ends, and with remote working encouraging more people to explore and use their local high streets more often, we are on the cusp of a significant shift in how our town and secondary urban centres are perceived and the role retail can play in their renaissance. In this Insight paper, Chapman Taylor Group Board Director Adrian Griffiths examines how our local high streets must adapt so that they can serve the purpose they did historically as vibrant, enjoyable and authentic mixed-use environments which are capable of evolving and thriving for decades to come.

Our town centres are experiencing an unprecedented series of challenges and changes, which the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated and magnified. Retail had already been in major decline for years, pre-COVID, but 2020 has laid the sector’s inherent problems bare like never before. However, the impact of COVID-19 or, more specifically, the government restrictions imposed in response to it, has also provided an insight into how our town centres can, and should, evolve.

Our local urban centres have become stronger as a result of the COVID-19 emergency, albeit at the expense of our city centres. The work-from-home phenomenon has currently reduced the need for people to travel beyond the areas in which they live, and local centres have provided those people with convenience and a sense of community when they needed it most.

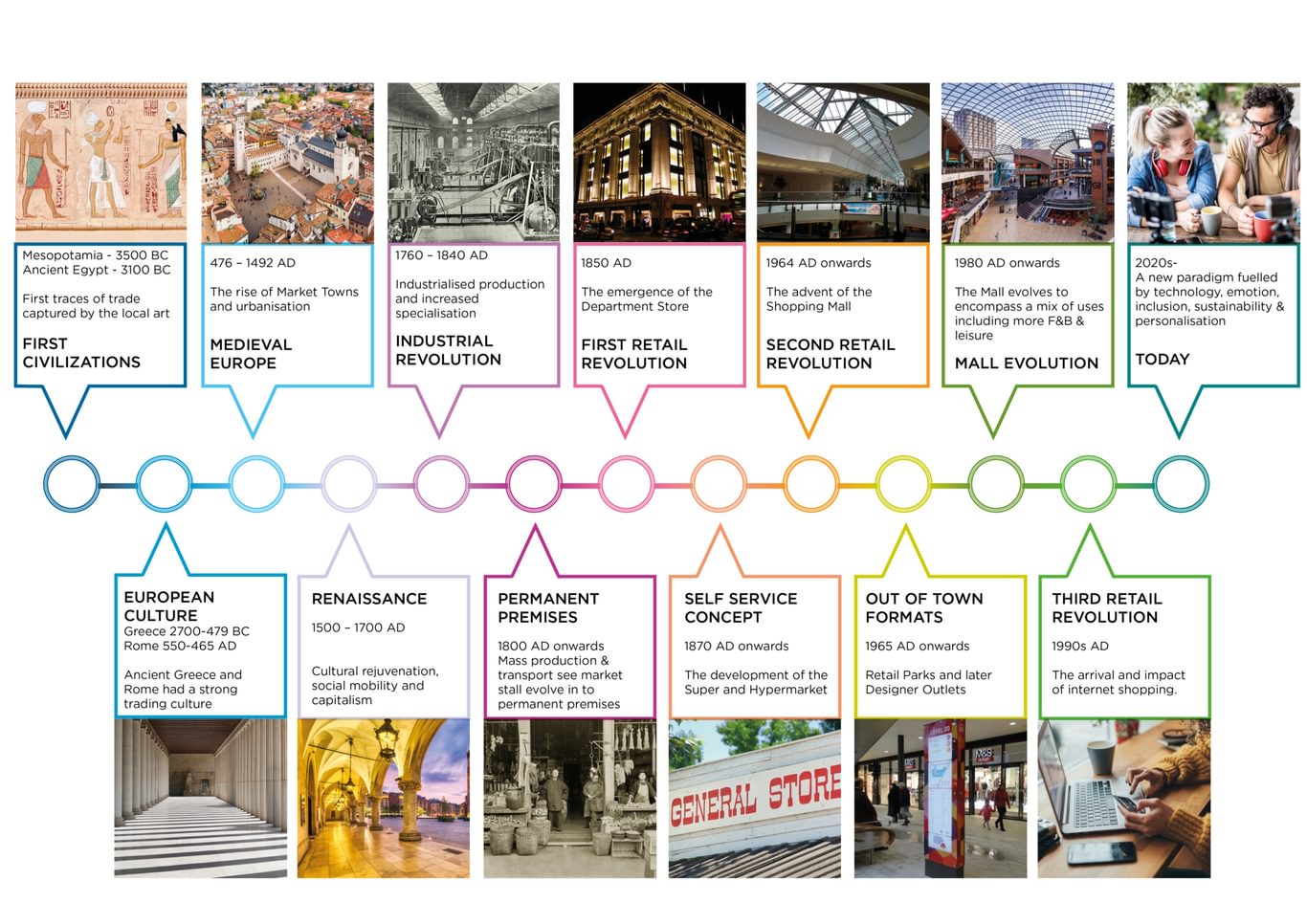

The evolution of retail

Back to the future

Our high streets were already in the process of going full circle and returning to the function they historically served when people generally lived, worked, socialised and shopped in their local village or town centres. The retail consisted of local independents, with butchers, bakers, fishmongers, ironmongers and other local trades and craftspeople all to be found on the local high street.

Markets popped up daily, with cattle markets taking place on a regular basis. The offer was authentic to its locality and reflected the seasons, while occasional fairs and circuses provided entertainment. Local suppliers evolved within these centres, supporting the industrial revolution. People innately understood how town centres should work and this ecosystem worked very well until the late 19th century.

And then along came the disruptors...

The arrival of department stores (mid-1800s), supermarkets (mid-1900s) and DIY stores (late-1900s) fuelled the process of our high streets being stripped of their local concessions, independents, ironmongers and food shops. Our centres were no longer places of convenience to which people would naturally migrate as a focus of their communities.

The arrival of the motor car in the late 1800s accelerated the suburbanisation process brought about by the building of railways, further depriving our town centres of their housing, industry, workplaces and retail.

Local authenticity was lost and was replaced by the arrival of the multiples and brands which started to dominate our high streets in the 1960s, peaking around 2007. These ubiquitous brands led to a significant growth in demand for larger retail units in what had been historic, finely urban-grained centres; this demand was met through the arrival of single / multi-level, enclosed shopping centres, which often stripped our centres of their heritage, authenticity and mix of uses.

Rental levels and business rates were then driven sky-high, backed by long leases. By the early 1990s, many of our town centres had become nearly entirely retail-focused identikit “cloned towns”, devoid of their original charm and sense of place. The high rents that large retailers were prepared to pay, and the perceived strength of their covenants, served to keep other independent uses away from the high street.

The arrival of the internet and online shopping started to impact the high streets in the 2000s, with shoppers beginning to embrace the convenience of browsing from home and having items delivered directly to their doorsteps. The internet accelerated the decline, which had already been underway for several years, in the requirement for physical banks, which were historically one of the reasons people visited town.

By 2008, cracks were appearing in the strength of the retail market and the financial crash exacerbated these problems, with the demand for town centre space starting to reduce. Rent levels also started to stabilise/drop, which, at last, opened the way for the introduction of other uses and, in particular, the food and beverage and leisure markets, which saw dramatic growth, taking up much of the vacated retail space.

The F&B market was now paying rents much closer to those of retail, but the continuing growth in online spend further undermined the requirement for a physical retail presence. However, by 2017, the F&B market became overheated, with many brands slipping into insolvency. At the same time, the public’s love for the department store model began to wane, partly because younger generations do not use or understand the format, and also because the older generations who do use them are declining in numbers.

Large-format supermarkets have become less attractive, which is clearly demonstrated by the rise since about 2014 of the basket shop and local convenience offers allowing people to shop for what they need on that day. For many, the weekly supermarket shop has become a thing of the past, with the public now tending to buy less food more often.

Princesshay in Exeter is a prime example of an integrated town centre where an excellent retail offer sits alongside well-considered leisure, F&B, residential, and community functions.

Where next for local high streets?

Our high streets have reached a crossroads. Fashionable new retail initiatives that might have been seen as a good idea a few years ago have already run their course. What has become apparent is that people inherently still understand that, fundamentally, our town centres are about providing convenience, experience and socialisation.

We mustn’t overlook the benefits of the internet for the high street, particularly that it can provide people with more time to spare, much of which may be outside the normal working day. This extra time is being used to socialise, take in an experience or browse/shop for convenience.

The gradual demise of the department stores will benefit the high street, with concessions and brands returning to buildings that represent their ethos. The growth of the basket shop will also help the return of independent butchers, bakers, etc. Even the DIY market continues to evolve, with brands such as Screwfix locating adjacent to, or in, certain centres.

We are beginning to see the growth of local independent retailers, bringing authenticity back to the high street, as well as pop-up activity, whether this be retail, food stalls, street food, fairs, markets or other offers, providing curated activity in our public spaces. It is common to see roads in town centres being closed for the day and artisan markets popping up on a regular basis. While department stores previously acted as retail anchors within our town centres, their role is now being replaced with the arrival of offers such as pop-up concepts, curated market buildings, medical centres and community uses.

Our town centres are at last beginning to be tailored to provide a more rounded local experience. It is not just about retail; people of all age groups want to live in, or close to, their town centres, to take advantage of what is on offer locally.

Understanding the future growth of the work-from-home format is still to be fully understood but, assuming there is a permanent move to more agile working, this is likely to benefit our local town centres, with people visiting them to work from cafés, gyms or local co-working spaces. There is now a great opportunity to reposition our town centres by building on their individual characters, authenticity and culture to provide a strong sense of identity, moving away from the clone towns of the past

However, this change is not going to be as easy, particularly when it comes to transforming the dominant enclosed shopping centre format, a subject that will be covered in a separate paper.

Facilitating the change

Our town centres now require much smaller shops, in locations that possesses a strong sense of place, with quality public spaces sitting at their heart. The centres need to offer architectural variety, taking their design influence from the locality, including the palette of materials used. The public realm, the space between the buildings, will need to be curated, and the management of the programme of activities will be crucial to the long-term success of the spaces.

The long-leasehold format is becoming a thing of the past and new short-term flexible leases will allow for regular changes to the retail offer, ensuring that our town centres remain relevant. Meanwhile, retail units will need to be flexible and simpler to fit out, reducing the costs when new tenants move in. The rental model also needs to evolve into a turnover model, giving the landlords an incentive to help their tenants to succeed – something which hasn’t always been the case in the past. The base rental levels must also be realistic, with valuations justified by local centres demonstrating they can consistently deliver an improving turnover, year on year.

Business rates for town centre shops are currently very costly and out of step with online retailing. The playing field needs to be levelled and business rates for physical locations should be calculated using a similar turnover model based on a low base rate with a performance-related turnover provision. Additional business taxes need to be secured from online retail transactions, which can then be fed back from the government to local authorities to help them balance their books.

We need to make sure we do not repeat the mistakes of the past to ensure longevity for our transformed high streets. To achieve this, we need to work more closely with local authorities, who will need to help provide the funding and incentives to support this long-overdue change, which up to now has been hampered by unrealistic retail asset valuations which are gradually being corrected.

City Centre South in Coventry is a new urban regeneration scheme with retail, new public realm spaces, a start-up retail and leisure pavilion, a premium cinema, new restaurants, private and rented residential accommodation and a hotel.

Putting the principles into practice

Chapman Taylor has long advocated the benefits of sustainable and integrated town centres in which an excellent retail offer sits alongside well-considered leisure, F&B, residential, office, hospitality and community functions. We have designed many schemes in accordance with this approach, having delivered such developments as Whitefriars in Canterbury, Princesshay in Exeter and SouthGate in Bath, to name but a few.

We are currently applying these principles on projects at two major UK urban centres with our designs for City Centre South in Coventry and the former Crompton Place shopping centre in Bolton.

In Coventry, we are working with Shearer Property Group in conjunction with the local authority to demolish 14 acres of post-war city centre development that has long passed its sell-by date, replacing it with a new series of legible streets and squares which will provide the framework around which we masterplan a mix of uses.

The old urban environment has primarily failed because it is all single-use, completely dominated by retail. The planning was very poor, with impaired permeability and a lack of legibility – office towers sit in the middle of streets! It is generally on a low scale, with a multi-storey car park taking up a significant amount of prime space. There are some listed buildings, such as the indoor market, which currently sits in a service yard.

Our proposal brings about a step-change by creating a strong sense of place with which the people of Coventry will bond. Among its provisions, the greatly improved urban environment will include retail, F&B, leisure and community uses to activate the street level, with a curated pavilion building in the heart of a new plaza, which will be fronted by the listed indoor market. A new hotel, medical centre, cinema and residential at the upper levels provide a rounded offer.

The architecture takes proportional material reference from the city’s past, while the development’s scale will not overly dominate, thus ensuring that the environment is authentic to the city. This project is a great example of the transformative change that can be achieved when developers, architects and stakeholders work collaboratively with the local council.

Bolton Victoria Place consists of a hotel, 150 homes, office space and a mixed-use retail, leisure, dining and events space (dubbed “Bolton Works”) .

Masterplanning for a mixed-use town centre community underpins Chapman Taylor’s design approach for Bolton Victoria Place. Working closely with Bolton Council, the strategy of Bolton Regeneration Ltd. is to compress and consolidate the retail core by demolishing Crompton Place to substantially reduce the retail floorspace. It will be replaced with a 1.5-hectare, open street development focused on reconnecting key streets with Victoria Square and opening new vistas to the magnificent tower of the Victorian town hall.

This new scheme supports the “whole place” approach of Bolton Council and includes a mix of complementary uses to create a town centre community of residential apartments, offices, a food-led multi-purpose market hall targeting local independent retailers and food operators, incubator space for business start-ups, community spaces, council services and a hotel.

By seamlessly extending and restoring the historic street pattern, the development creates four distinct urban blocks, reconnecting Victoria Square to Bradshawgate and focusing views to the town’s greatest visual asset, its town hall. The scheme reintroduces several streets previously removed by the existing shopping centre.

Each block provides a distinct mix of uses above an active ground floor. New offices are located opposite the town hall and a new residential community is nestled above two of the blocks in the heart of the scheme. The centrepiece will be the new Bolton Works artisan food and makers’ market building, which will provide flexible space for independent, local start-up businesses. The upper levels of this building will also provide space for use by the community for events, exhibitions and showcasing the town’s community groups.

Importantly, each urban block is designed for flexibility, enabling the uses to be changed and adapted without the need to disrupt or change the underlying masterplan and network of streets. This will allow the buildings to respond to future changes, market demands, community requirements and customer expectations without the need to resort to wholesale demolition.

Both of these redevelopment projects build on our extensive experience and will deliver state-of-the-art, mixed-use environments that will stand the test of time and of which local residents can be truly proud.