Rethinking airport terminals: Traditional customer service values in the digital age

Airports are intense microcosms of the commercial world in general – particularly in relation to retail provision – and, just like the wider retail sector, airports are having to cope with the challenge presented by online retailers and transformed customer preferences. In this Insight paper, the first of a series of three, Chapman Taylor UK Associate Director Luke Kendall suggests that, rather than airports being threatened by these changes, they are ideally placed to take advantage of the new reality and can draw inspiration from responses in the wider retail world. He argues that what is needed is a new, physically seamless terminal environment where cutting-edge design thinking combines with time-honoured customer service values.

Harry Selfridge had an underlying philosophy that his store shouldn't be seen simply as a 'shop' where he sold 'stuff'. He was passionate about Selfridges being a social and cultural centre, one where people could commune, relax, browse and simply enjoy the experience.

“Treat [the customers] as guests when they come and when they go, whether or not they buy. Give them all that can be given fairly, on the principle that ‘to him that giveth shall be given’.”

In the first of three papers, we seek to answer a question that we are regularly asked by airports, namely “Where is terminal retail heading?”.

Prior to the impact of COVID-19, the Airports Council International (ACI)[1]was reporting an increasing reliance on non-aeronautical income to achieve profitability[2]. It is unlikely that the post-pandemic environment will see any change in this tendency, and airlines will need to find new ways to achieve profitability themselves as we are unlikely to see much of an increase in aeronautical income.

Despite longer dwell times, retail within airports, as with the wider retail sector, was already under pressure from online competition. At least in the short term, COVID-19 is likely to present further challenges for the commercial offers within airports, with increased processing and the continuing requirement to maintain social distancing. In some respects, however, the changes already in train pre-pandemic may provide solutions for some of these issues.

Chapman Taylor is committed to research and continual development to ensure we provide best-in-class design advice to our clients, helping them to manage change, whether it is regulatory, socioeconomic or technological. Our Retail and Mixed-Use Team has produced a number of Insight papers on the future of retail and the necessity of a well-considered mix of uses, post-COVID, to revitalise former department stores, high streets and other struggling, retail-led developments. Many of the principles outlined in these papers are applicable to the future direction of Aviation.

Relevance

Much of what is played out in the wider commercial sector, particularly retail, will have a resonance in an airport terminal context. The transportation function adds complications to the commercial landscape, such as stress, the need for dynamic information and the fact that it is inherently a transitory environment.

Research[3] has shown that as many as 75% of purchases in a terminal are planned and as few as 25% of travellers intend to shop when passing through an airport, with only 40% intending to eat. On average, half of these purchase decisions have been made before a passenger leaves home.

Once at the airport, while most customers’ F&B intentions carry through into actual purchases, almost half of intended retail purchases are not fulfilled. This is due to a number or stated reasons, including:

(Those who had planned to purchase)

- 53% did not find what they wanted

- 1% quality

- 28% too expensive

- 9% did not want to carry

- 5% did not have time

- 2% queues too long

- 1% lack of choice

(Those who had not planned to purchase)

- 70% not interested

- 1% queues too long

- 10% too expensive

- 7% did not want to carry

- 7% did not find what they wanted

- 3% did not have time

- 1% lack of choice

Recently, therefore, we have been working with airport operators to focus on closing the fulfilment gap as much as increasing the propensity to spend. Airports’ dependence on the income from their commercial offers has required them to continually evolve to maintain that income. As in the wider mall market and on the high street, we have seen demand for F&B increase. However, while F&B options help to fill the growing retail void, reliance on F&B alone is not sustainable.

Airport income is now under further pressure. Income-per-passenger is increasing in some airports but, arguably, this is where a low baseline existed previously or where there has been significant investment in new attractions. However, in many mature environments, growth in non-aviation income is often a mirror of the growth in passenger numbers, with falls below that growth line signifying a reduction in propensity to spend

A terminal is different from a mall of high street in several key ways, especially in that it has captive footfall, but it is also a transitory space and a means to an end.

Change and Response

As well as the impact of the internet, customer desires and attitudes have changed as generations have changed and as younger people with different outlooks become spenders and influencers.

The challenge is for us to develop a new model that will attract interest, patronage and dwell – an environment where people want to be as an added experience rather than just passing time while on the way to somewhere else. It will demand much more effort and commitment from operators and will require new commercial arrangements between the operator and commercial partners, as well as between airports and airlines. These arrangements will be less point-of-sale transaction-orientated and more about synergetic business case sharing and cooperation.

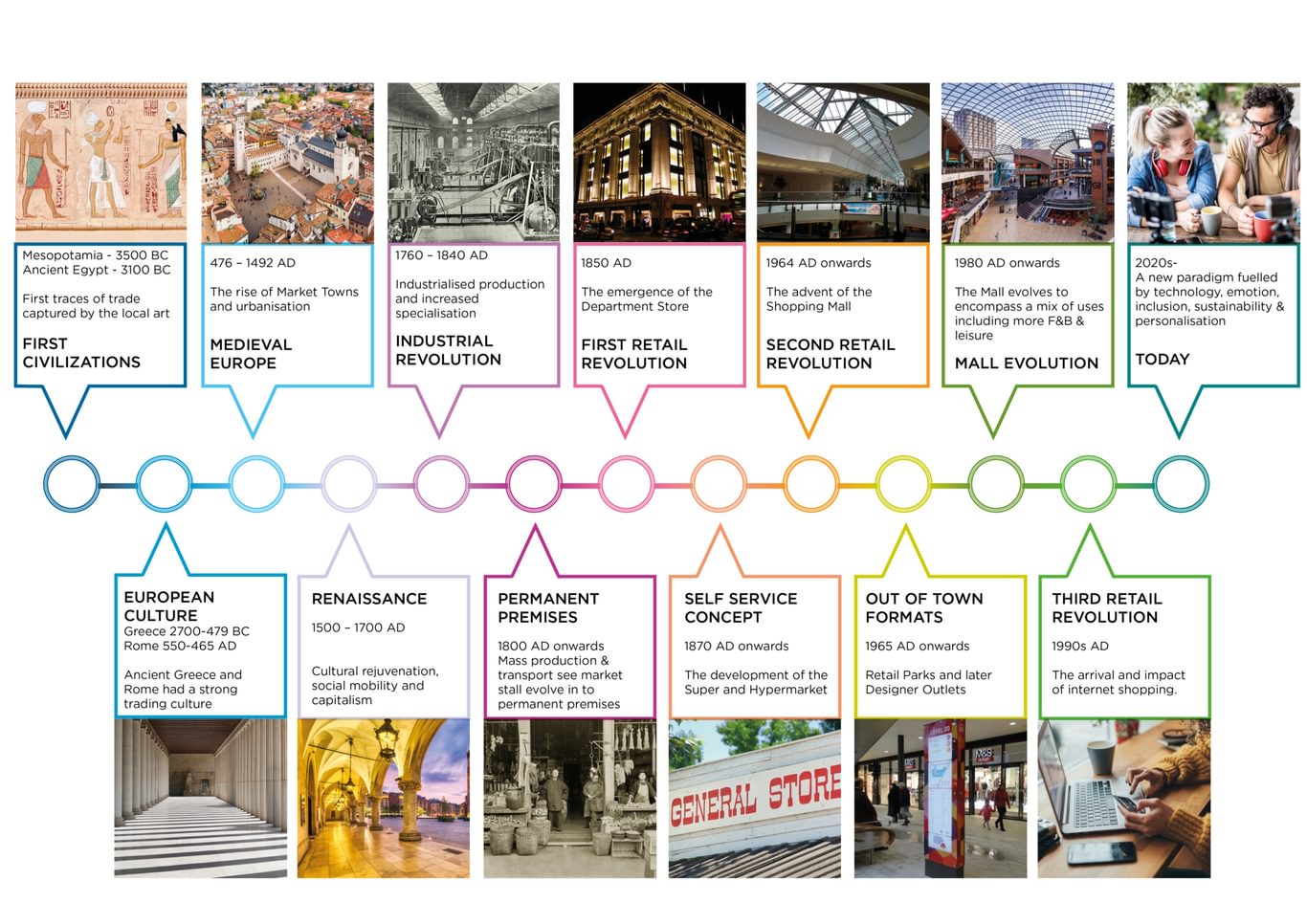

Many responses to the wider challenge already exist and, while we should always look for new ideas, we should also look to these existing ideas to help airports develop an exciting, curated environment.

The starting point is not only to understand the wider demographic trends but also those specific to each airport and terminal. Each solution will need to be tailored and also be able to adapt easily to maintain relevance. Much airtime has already been given to the need for curation – the need for the operator to manage the environment and its offer more along the lines of a gallery with its permanent and temporary collections. A terminal may therefore develop its own brand identity, based on some core principles, but with components which facilitate a targeted approach.

Core Principles

Some fundamental elements will be the need to create a sense of experience, entertainment, personalisation and ease of navigation, both physically and virtually.

Digital: We are only just starting to explore the potential of digital media to advertise, entertain and interact with. This technology is rapidly evolving, including interaction with personal devices and the growth of augmented reality technologies.

Personal technology: While we need to try to divert passengers’ eyes away from their smartphones, those phones are here to stay as an important commercial consideration. We therefore need work with all the terminal’s partners, including airlines, to provide a seamless, one-stop experience that doesn’t require hopping from one app to another. People are becoming loyal to the brands that are smartly using technology to simplify every aspect of our lives. The brands that do it best will create experiences that have you asking how you ever lived without them.

Experience: Commercial environments need to be entertaining, experiential and relevant. As well as including many of the other aspects noted here, key components should be innovation and exhibition. Exhibition pieces could be architectural, artwork or even product demonstration.

Sense of place: Intrinsic to the experience is the creation of a sense of place; architecture is the core component of that, but the skilful layering of everything else will dress the stage set by the architecture. The composition must establish an emotion of belonging and of feeling comfortable, eliminating stress and alienation.

Variety: The experience needs to meet the desires of the customer and include churn. Churn is often seen as being limited by the requirements of secure regulatory environments, but we need to find ways to make it work. A variety of interesting pop-up local offers may present a logistical challenge, but some of this effort and cost should be borne by the airport to enable the greater long-term benefit while demonstrating commitment to local communities and economies.

Blending: We will see more blending of companies (work drop-downs mixed with F&B and retail), and the boundaries of dwell, entertainment and commercial areas will blur, potentially disappearing completely.

Senses: Airport environments will need to appeal to all of our senses. The visual is obvious, but we should consider temperature, air quality, lighting levels, sound and smell as well. Why not consider the introduction of a spice market in an Asian airport, for example, with all its colour, tastes and smells? Or a restaurant attracting interest through zoned music, the clatter of kitchen activity or the fragrance of the food? There is a good case to be made that airport terminals are currently too clinical and homogenous.

Showrooming: This is a key area where the new partnership business model comes in, where partners may be showing off their wares, but the transaction occurs elsewhere or virtually. Increasingly, people are using down or travel time to explore, and airports can respond to this for passengers but will need to agree new, mutually beneficial deals with commercial partners.

Personalisation: We need to use tools, including personal technology, to create a sense of personal care and attention which permeates the culture of the whole terminal experience, including the required processes. We are likely to see an increase in person-to-person customer care and less of the “move along now” sausage machine attitude. Processes don’t necessarily have to change, but modes of interaction might.

Sustainability: People are increasingly concerned about the provenance of the goods and services they buy and consider their sustainability and ethics in more and more detail.

Ingredient examples

To broadly summarise, customers are seeking a varied, personalised experience which is relevant to their values. For the younger generations, these values are increasingly embodied in principles such as sustainability, authenticity, inclusivity and interactivity.

All of this will be increasingly channelled through digital technology and through the culture and quality of the spaces we create and manage with partners. We can broadly group some examples of responses to these challenges under a series of typologies that inevitably cross over between each other.

Below, we explore just a handful of examples that touch on these key ideas, whether respond to broader or narrower markets. We can learn from, adapt or directly copy these ideas, but the goal here is to give a flavour of possible responses rather than a strict prescription.

- H&M’s store in Hammersmith, London, is more akin to an aspirational shopping experience, while also tapping into the sustainability trend. The shop is full of sustainable messages, including greenery, and there is a ‘Repair and Remake’ station which encourages customers to recycle garments. It’s free for customers who are part of the H&M Club loyalty scheme and it offers personalised embroidery. Key elements: Sustainable, Provenance and craft, Showroom, Personalisation

- Belstaff on Regent Street encourages customers to bring in old jackets to be repaired, and customers can enjoy an in-store coffee or a gin and tonic from its own bar. This same space hosts classes on how to take care of leather and waxed clothing. This is about putting the customer first and building a brand community. Key elements: Blending, Sustainable, Provenance and craft, Showroom, Personalisation

- US furniture and homewares retailer Crate and Barrel has opened a restaurant in its Chicago store, partnering with a local chef. The feature keeps customers in store for longer and ‘The Table at Crate’ customers actually use and experience many of the items on sale, from furniture to cutlery. The restaurant is also used for other activities outside of restaurant hours, such as cooking demonstrations. Key elements: Blending, Provenance and craft, Showroom, Entertainment and education

- The ethos behind Eataly is “Eat, Shop, Learn", and the company creates an accessible experience that encourages all guests to eat sustainably sourced fare with quality ingredients, shop for the best local and Italian products and feel empowered to learn about Italian culture and cuisines. Key elements: Blending, Sustainable, Provenance and craft, Showroom, Entertainment and education, Personalisation

- Alexander McQueen’s store on Bond Street, London, as well as displaying the latest collections from the retailer, also features archive designs as another way to drive footfall. Photographs and artworks are displayed throughout the store, with the top floor entirely dedicated to showing the history of the brand and the stories behind specific designs. The store also hosts talks and exhibitions to inspire students and customers, foster new talent and demonstrate the company’s commitment to the industry. Key elements: Provenance and craft, Showroom, Personalisation, Entertainment and education

- Intended to help build customer brand loyalty, Audi opened an ‘innovation space’ in Hong Kong’s Festival Walk mall that uses virtual reality (VR) to take customers on a journey, allowing them to explore customising the full range of models, including future concepts, and even to take them for a test drive. Key elements: Showroom, Personalisation, Entertainment and education, Wellbeing and action

- The Cos in Coal Drops Yard shopping area in Kings Cross entices customers into the hybrid space with a curated experience of work from both established and emerging artists. As well as curating its own collection, it offers limited edition prints, a selection of books and other products from brands with a story to tell. This is again aimed at immersing customers in the lifestyle of the brand. Key elements: Blending, Sustainable, Provenance and craft, Showroom, Personalisation, Entertainment and education

- Samsung’s new space in Coal Drops Yard is essentially a marketing space for the brand. There are no tills, and instead the space is packed with experiential retail, including gaming lounges, co-working spaces, DJ booths, an events space and personalisation bars in which people can design their own products. It also features a digital graffiti wall, a ‘kitchen of the future’ and a travel photography workshop. Key elements: Blending, Showroom, Personalisation, Entertainment and education, Wellbeing and action

- Chanel in Paris focuses on the customer in the shop, but in conjunction with the Chanel app. Chanel has partnered with Farfetch to trial tools that use data to create personalised shopping experiences. The two top floors of the store are dedicated to VIP customers only, with personal styling rooms and a restaurant exclusively for private meals. Key elements: Blending, Showroom, Personalisation, Entertainment and education

- German-Swiss bag brand Freitag has opened a micro factory store in Zurich’s District 4. Customers have the opportunity to create their own one-of-a-kind version of the brand’s famous tarp bag. The bags are made from recycled truck tarp and fully compostable textiles. The space provides visitors with an engaging and unique experience but also educates them on the sustainable manufacturing processes that the retailer is passionate about. Key elements: Sustainable, Provenance and craft, Showroom, Personalisation, Entertainment and education

- MUJI has launched a design and retail pop-up store in New York’s SoHo. The space showcases the design history of the brand, as told through classic MUJI products from its archive and an exhibition of its posters throughout history. It also promotes its global initiatives, including the MUJI hotel and MUJI diner. Key elements: Provenance and craft, Showroom, Personalisation, Entertainment and education

- Italian furniture brand Natuzzi has launched a virtual reality shopping experience. Customers can enter a digital drawing of their own home and decorate it with Natuzzi pieces. Customers interact with the environment and move furniture around, as well as changing the colour of items. They can view a scaled down hologram of their home on a tabletop for a birds-eye view of the space. Key elements: Showroom, Personalisation

- Nike’s House of Innovation store in New York aims at customers seeking experiences. Structured around the Nike app, customers can virtually shop in the store through their phones, personalise items and use instant checkouts. They can try out some new trainers and even shoot some basketballs. Key elements: Showroom, Personalisation, Wellbeing and action

Conclusion

Imagine a lounge akin to a private club, with its subtle blend of familiarity and anticipation – a place where you can relax, eat and drink, with a VR theatre in which to try out the latest sports car or mountain bike or to visualise yourself in a makeover. It will be place where, through physical and virtual interaction, you have a personalised, stress-free experience that you enjoy rather than merely be processed through.

Such a deeper engagement with passengers would enable airport terminals to build better connections and repeat custom for the airport and, importantly, the airport’s partners.

In this vision, the airport terminal is more akin to the steward of a platform for partners, helping them to build relationships within the airport umbrella. It is therefore necessary that airports and retailers create well-considered and proactive partnerships.

For architects, the challenge is to move airport terminal design away from strict lines of use and tenancy types and work with the airport to create an enabled, vibrant, flexible sense of place.

While high street department stores may be in difficulty, there is still a strong resonance in Harry Selfridge’s original ideas; while the model may have lost its way, it could find a new relevance in the 21st century aviation sector, with the principles of respect and customer focus being repurposed for a very different environment.

[1] ACI Airport Economics Report

[2] These findings are from a cross-sector survey and exceptions exist.

[3] Combined sources; DKMA Airport Consumer Survey, Institute of Retail Studies University of Stirling and DKMA Airport survey of departing passengers.