From sketch to reality: Jan Pokorny on using sketching as a form of dialogue

As a concept design specialist, Prague studio Associate Director Jan Pokorny uses his excellent free hand sketching skills to create and develop designs for a wide range of building types, including some of the most memorable projects on which Chapman Taylor has worked in recent years. Using a range of projects from the last few years, Jan explains here the benefits that sketching provides, how he uses sketches as a form of dialogue with clients and others and why the finished buildings often maintain the spirit of the early concept sketches.

Where do you start when creating a concept sketch?

A concept design always begins with some essential information already in place to inform the kernel of the idea, whether it’s the client’s vision, the functions, the applicable local / national rules, the climate or the surrounding context. I usually start by examining the site location, which always gives me ideas about the appropriate volumes and design directions, such as the colours, materials and feel of the building.

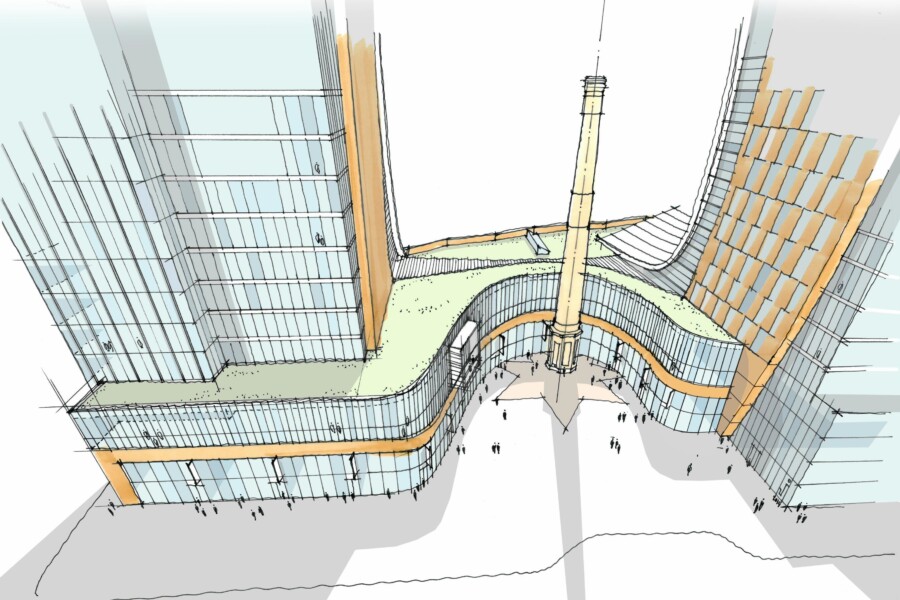

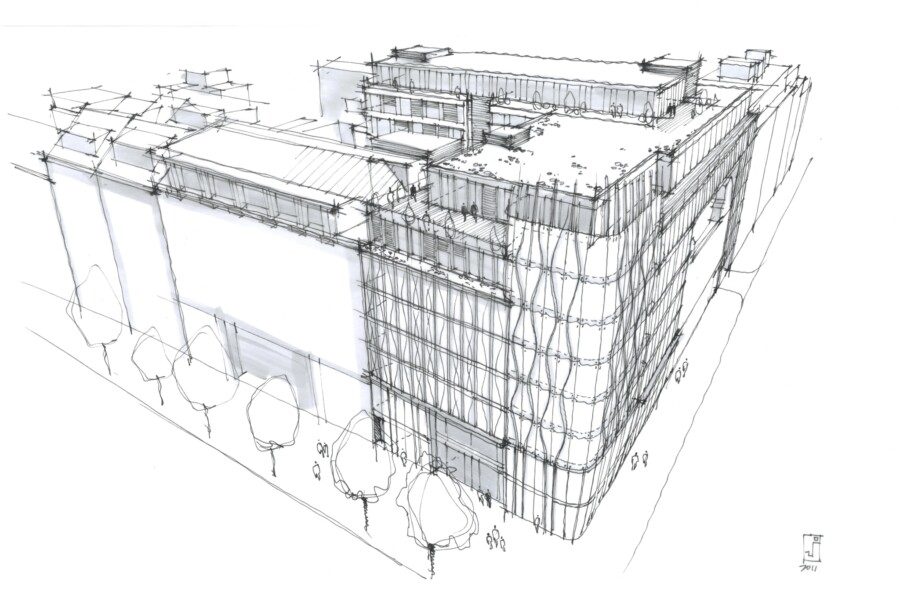

For the Flow Building on Wenceslas Square in Prague, for example, the surrounding buildings helped inform the façade design – we wanted to create a thoroughly modern building with the best technical parameters. Through the massing, understanding the typology of corner plots on the square and thinking carefully about the materiality, we were able to visually integrate the building within the historic urban fabric.

If I can’t visit the site in person, I will look at something like Google Maps to get a 3D sense of the area. I then start to sketch initial volumes with a pen or pencil. Alternatively, I use a CAD plan to look at area sizes and basic volumes and then generate a basic 3D model with the appropriate building volumes in SketchUp, taking account of proportionality, horizons and other elements. I later add façade details via free hand sketching and play further with the shapes and composition.

I always create several sketch options to provide clients with a range of architectural strategies from which to choose and to inform further ideas from them. Sometimes I might not actually like one of the options, but I think it is important to include it so that the client gets a full picture of what is possible, even if only because they might want to incorporate one or two small elements from that design. Further discussion with the clients then results in a stronger focus on one or two of the design options, allowing me to concentrate more on the detail of the design.

The initial sketches form the basis for further dialogue with clients and others?

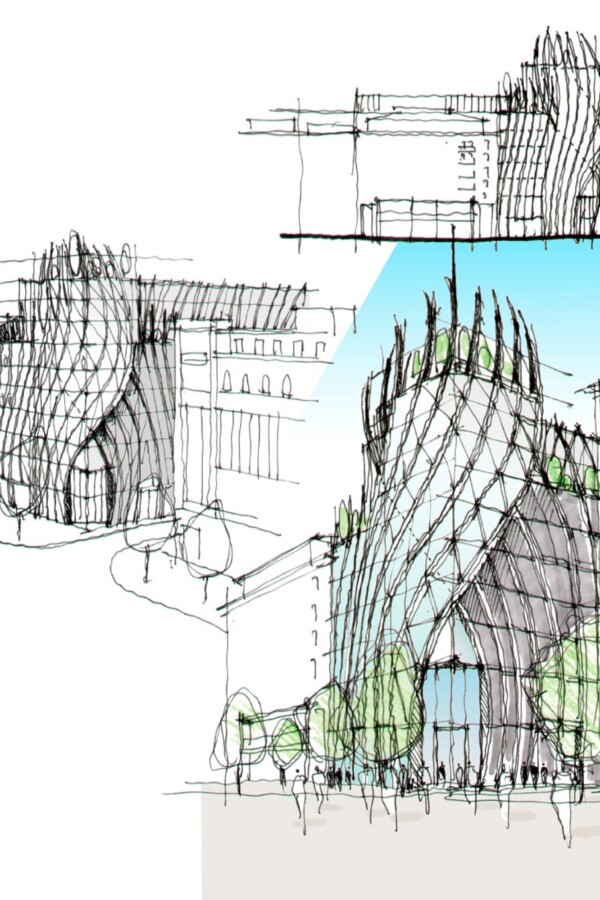

The initial sketch options are presented to the client and other relevant stakeholders for their feedback. The great advantage of sketching at this stage is that it is such an easy, cheap and fluid process, allowing for a visual dialogue to take place at speed. Ideas can be sketched during a meeting and be immediately commented on by any of the parties, providing a very efficient means of progressing the design and narrowing down options.

What do you use when you sketch?

I usually use detail paper and a pencil when I start sketching. I then develop basic CAD drawings to check areas, shapes and proportions, from which I generate the volumes in SketchUp to add details and create the fundamental design. SketchUp is a wonderful tool – much faster and more accurate than setting up a perspective by hand. When I worked in Australia several years ago, there was no SketchUp, meaning I had to draw the geometry using very large pieces of paper, and it was a slow process to get the main massing elements right.

Why is sketching useful?

Free hand sketching is very flexible and allows you to create several options very quickly. At the beginning of a project, it is not good to be very precise and detailed, and sketching allows you to “hide” elements which are yet to be determined. The imprecision can itself generate new and exciting ideas about possible materials and shapes.

In addition to speed and flexibility, clients respond very well to the personal, human touch of sketching – they appreciate seeing sketches more than computer-generated images, which can sometimes seem sterile and “too perfect”. You can put a good sketch in a frame and it makes a very interesting picture, whereas a framed CGI would be less of a talking point.

Finally, sketching with a pencil and paper is very cheap! For the early stages of the design process, several options can be developed and refined while adding little to the project’s costs.

Do you compare your early sketches with the completed and occupied building?

I quite often find that there has been very little fundamental change between the finally chosen sketch option and the finished building, with perhaps just relatively minor details being refined and clarified. I think that this is because I create the sketches using accurate volumes and scales. For example, at The Flow Building, the volumes, heights and proportions of the buildings are almost exactly the same as drawn in the early sketches.

The similarities can also be explained by one of the principles I try to apply to the projects I work on, namely that I don’t compromise very much on the principles of the design. Once the design is agreed, clients and contractors can sometimes try to push new, often unnecessary changes, particularly during the construction phase, which undermine the integrity of the design and can lead to problems later on. It is important to act as a guardian of the design, right to the end of the project, and ensure that the original intent is not lost, which is what we have hopefully achieved with the Flow Building.

Do you get satisfaction from seeing the completed buildings being visited and used that once only existed on a piece of paper on your desk?

It’s quite special to see the sketch become a reality, particularly after spending several years bringing a project to life, as with The Flow Building, on which I worked for 12 years.

Some people love a building like The Flow Building when it is built, and others dislike it, but good architecture should arouse strong emotions rather than create something bland and unremarkable about which nobody cares.