Achieving Net Zero: Six Simple Steps

Chapman Taylor’s in-house Responsible Design Group was set up to improve awareness and knowledge of good sustainable design across our UK and international studios.

Net Zero, and the reduction of carbon emissions, is a fundamental part of our Responsible Design agenda but is not exclusive of other important facets such as Community & Social Value, Connectivity and Ecology.

Here, associate director Daniel Morgans summarises our thoughts on achieving Net Zero, which will provide a conduit to other such thought papers on the six steps.

The Challenge

We are living in a climate emergency. To preserve a safe, prosperous, and liveable planet, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions need to reduce by 45% by 2030 and reach Net Zero by 2050.

The UK building industry has a significant part to play in leading this change. It is responsible for 40% of carbon emissions and is still traditional in its approach to how buildings are created, with materials such as brick, steel, concrete and glass the default choices.

‘The building industry consumes almost all the planet’s cement, 26% of aluminium output, 50% of steel production and 25% of all plastics.’

These all generate enormous amounts of carbon in their creation, but some innovation is mitigating this. Only timber and stone as primary structures are ‘carbon-light’, but their uptake is problematic due to (the perception of) fire resistance and versatility. Therefore, the challenge is a holistic one, and every part of the construction process must be considered through a Net Zero lens.

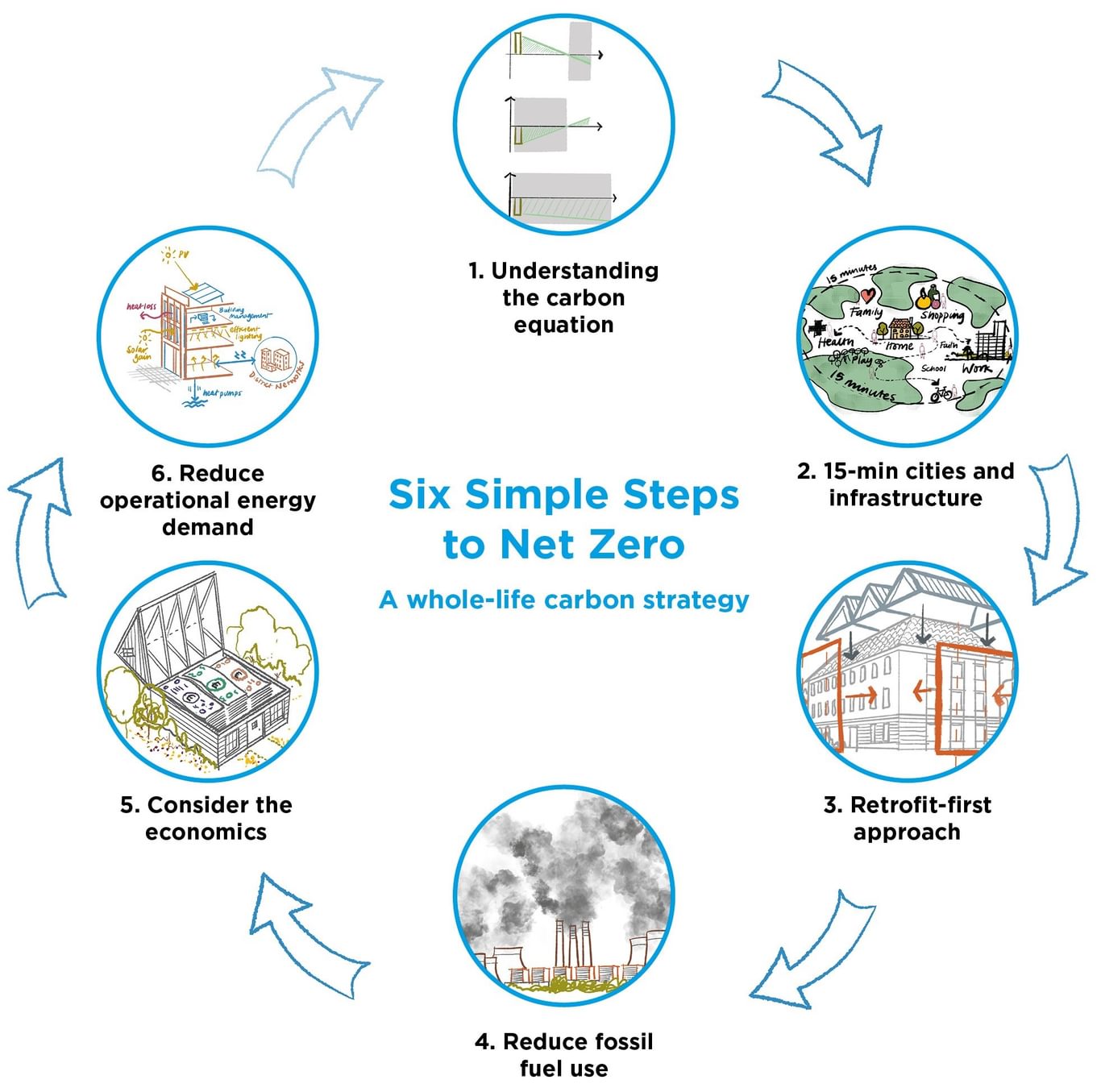

Six Simple Steps

The steps to Net Zero are not exhaustive, nor are they as simple as this paper suggests! However, in trying to understand the challenges, it is important to assemble component parts in a clear, concise way so that the entire building team can understand the 'big picture' from the outset:

1. What is Net Zero?

The construction industry takes a holistic view of ‘whole life carbon’ by including embodied and operational carbon emissions in one calculation. Therefore, the energy used in creating a building conflates with the energy used in operation and is offset against energy creation from renewables, or carbon offsetting.

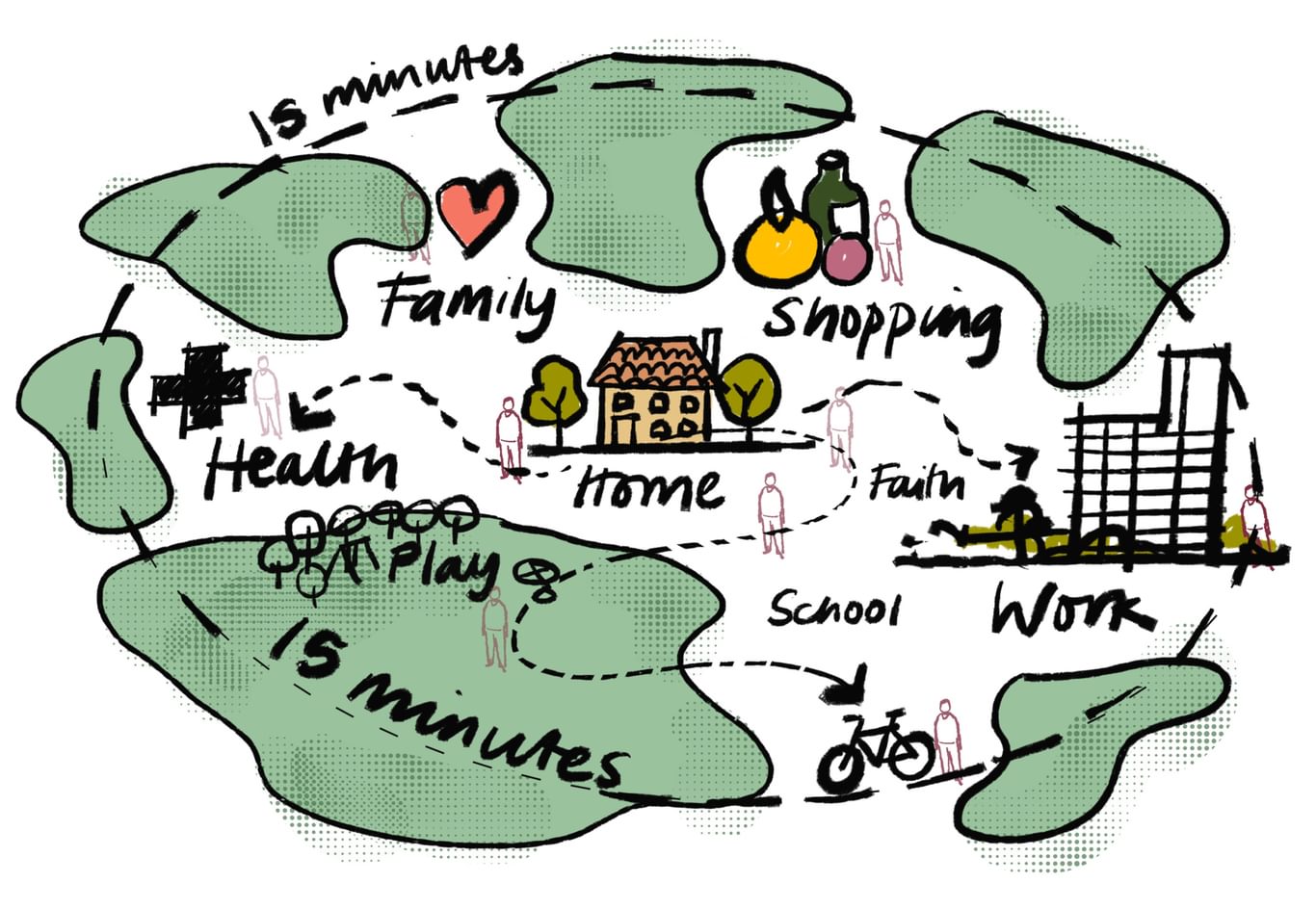

2. Creating 15-minute cities and reduction in infrastructure

Building design starts at the macro level. It is important that masterplanners and Local Authorities consider their local plans in the context of the associated infrastructure costs of low-density design. Initiatives such as the Velocity movement and the 15-minute City (Carlos Moreno) address this by increasing the density and accessibility of everything we need within a tighter radius.

3. Retrofit-first

By encouraging clients to assume a retro-first attitude when considering a change of premises (predominantly for offices, but this could also apply to industrial and housing association landlords) the associated effects could be significant conservation of embodied carbon. Retrofitting an existing building is always a complex challenge, but the savings in carbon from the materials and construction process can make this worthwhile.

4. Cut fossil fuels

Organisations such as Energy Saving Trust encourage district heating with hydrogen gas, solar water heaters and electric heat pump plants in an urban-wide approach. Reductions can be made by discouraging the use of high-carbon fossil fuel technology, such as gas boilers.

5. Consider the economics

Aside from our duty to de-carbonise, there is also a financial incentive for a low-carbon future. Organisations such as the Taskforce for Climate Financial Disclosure effectively support energy performance data so that clients can assess risks associated to climate change. Poorly-performing assets can become financially stranded (unlettable or unsellable) so the imperative is ‘stick’ as well as ‘carrot’!

6. Reduce operational energy demand

This is where the application of architectural technology and well-considered design is key, with organisations such as LEED, Passivhaus and Nabers leading to solutions. By reducing energy demand, not only is there a cost saving but critically also a saving in operational carbon, which has a greater effect on Net Zero over the life of an asset:

• Passive design optimisation: the orientation and the associated solid-to-void ratio of specific facades. Careful application reduces cooling loads, heat loss, glare and enables partial natural ventilation.

• Balancing a ‘building fabric first’ approach against embodied carbon by using passive lighting and cooling (as above), ‘build light’ and reviewing drivers of energy consumption.

• Building management: careful handling of data and the flow of energy through a building to optimise heat gain and loss, control lighting levels and constantly monitor performance.

7. Consider whole-life carbon

With disclosure and openness in building performance data, greater impact can come from looking at the whole life of an asset, from inception to potentially re-use or disposal. It is about having the mindset to consider carbon in every part of the lifecycle, rather than at its creation.

With initiatives such as modular design technology, buildings can become more flexible, so that they can be adjusted and changed throughout their life with minimal impact.

https://www.un.org/en/climatec...

https://energysavingtrust.org....

2. Creating 15-minute cities and reduction in infrastructure

Building design starts at the macro level. It is important that masterplanners and Local Authorities consider their local plans in the context of the associated infrastructure costs of low-density design. Initiatives such as the Velocity movement and the 15-minute City (Carlos Moreno) address this by increasing the density and accessibility of everything we need within a tighter radius.

3. Retrofit-first

By encouraging clients to assume a retro-first attitude when considering a change of premises (predominantly for offices, but this could also apply to industrial and housing association landlords) the associated effects could be significant conservation of embodied carbon. Retrofitting an existing building is always a complex challenge, but the savings in carbon from the materials and construction process can make this worthwhile.

4. Cut fossil fuels

Organisations such as Energy Saving Trust encourage district heating with hydrogen gas, solar water heaters and electric heat pump plants in an urban-wide approach. Reductions can be made by discouraging the use of high-carbon fossil fuel technology, such as gas boilers.

5. Consider the economics

Aside from our duty to de-carbonise, there is also a financial incentive for a low-carbon future. Organisations such as the Taskforce for Climate Financial Disclosure effectively support energy performance data so that clients can assess risks associated to climate change. Poorly-performing assets can become financially stranded (unlettable or unsellable) so the imperative is ‘stick’ as well as ‘carrot’!

6. Reduce operational energy demand

This is where the application of architectural technology and well-considered design is key, with organisations such as LEED, Passivhaus and Nabers leading to solutions. By reducing energy demand, not only is there a cost saving but critically also a saving in operational carbon, which has a greater effect on Net Zero over the life of an asset:

• Passive design optimisation: the orientation and the associated solid-to-void ratio of specific facades. Careful application reduces cooling loads, heat loss, glare and enables partial natural ventilation.

• Balancing a ‘building fabric first’ approach against embodied carbon by using passive lighting and cooling (as above), ‘build light’ and reviewing drivers of energy consumption.

• Building management: careful handling of data and the flow of energy through a building to optimise heat gain and loss, control lighting levels and constantly monitor performance.

7. Consider whole-life carbon

With disclosure and openness in building performance data, greater impact can come from looking at the whole life of an asset, from inception to potentially re-use or disposal. It is about having the mindset to consider carbon in every part of the lifecycle, rather than at its creation.

With initiatives such as modular design technology, buildings can become more flexible, so that they can be adjusted and changed throughout their life with minimal impact.

#NetZero #NetZeroCarbon #ResponsibleDesign #Sustainability #SustainableDesign #CarbonEmissions #ClimateEmergency #GreenhouseGas #BuiltEnvironment #WholeLifeCarbon #15MinuteCity #15MinuteCities #Retrofit #Decarbonise #Masterplanners #Masterplanning #Architects #Architecture #Design #Designers