Healthy Streets: The street and buildings

Chapman Taylor’s Transport & Infrastructure team provides support on many of our mixed-use urban development projects, which require a progressive, joined up, multi-sectoral and multidisciplinary approach.

COVID-19 has triggered a step-change in how we design the urban public realm and how that interfaces with transport infrastructure and functions. In a new series of Insight papers by Chapman Taylor UK Transportation Director Peter Farmer, we explore five interlinked aspects influencing our approach:

- Rebalancing the street: a shift in street priorities

- The “Elastic Street”: the need to reconnect with our environment and transport options

- The new wave cycling boom and its impacts

- The street and buildings: new demands of the interface with the public realm

- Street charging: accommodating e-cars and bikes in urban residential streets

In this fourth paper, we explore how Healthy Streets and associated social changes are starting to influence the interface between street and buildings.

Much of the focus of the Heathy Streets initiative is on transport and its interface with the public realm, which has both direct and indirect impacts on the design of buildings.

There are also strong synergies between Healthy Streets and the increasing trend towards encouraging mixed-use development to bring life and vibrancy back into our towns and cities. Mixed-use takes many forms, mixing vertically, horizontally or both. The principle is a core element of the “15-minute city” ( ___ad link____ ), reducing car ownership and increasing engagement with the public realm of the street ( ___ad link____ ).

In urban areas, the blending of uses creates an interesting sense of place, providing numerous places to shop, dine, work, live and gather. While this happens more organically in built-out urban areas, we’re also seeing it happen in new mixed-use projects

Neighbours

Establishing a vibrant 18-hour day / evening environment may be our goal, but we need to consider how the uses mesh with the pattern of use throughout the day, a process made more complex by increasing numbers of people working from home. The murmur of conversation from a restaurant may be music to some, but it may keep others awake. Although where we live or work is our choice, building design can help. For example, we can arrange bedrooms towards the quieter areas or design façades to baffle sound from different uses.

Orientation and planning are key for managing overlooking and sightlines while recognising the value of visibility to community policy and safety.

The term “informal social control” is commonly used to refer to the maintenance of order by members of the public or of a particular community. In 1961, Jane Jacobs[i] pointed out that routine surveillance by people going about their daily business tended to reduce the incidence of transgressive, anti-social or criminal behaviour. She also advocated mixed-use public space to maximise the number of public eyes and ears engaged in this practice.

Spill

A major benefit of the Healthy Street policy is enabling activity to spill out into the open air. Street scape activity wether commercial or just social is seen as increasingly important to social cohesion as Louis Kahn wrote; ‘The street is a room by agreement, a community room, the walls of which belong to the donors, dedicated to the city for common use. Its ceiling is the sky. Today, streets are disinterested movements not at all belonging to the houses that front them. So you have no streets. You have roads, but you have no streets.’[ii]

By allowing and actively encouraging spill on to our streets we will also improve a sense of ownership, care and security.

Access and facilities

Interlinked with other trends and policies will be pressure to provide new facilities at the junction between inside and out, i.e. around entrances.

With more people walking, cycling or running to work, in all weather, we will need to increase the provision of amenities for managing cycles, showering and changing. One potential impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic is that occupants and tenants may demand dedicated facilities rather than the communal services currently provided by most landlords.

In residential developments, we may see the increased popularity of wet rooms, utility rooms or “boot rooms” at entrances. We need to give more consideration to cycle storage as well. Local authorities already put a lot of emphasis on adequate, safe, secure and accessible cycle storage within all types of development. Quality cycle storage could well be a market differentiator for residential developers.

As we touched on in our paper about the new wave cycling boom, micro-mobility customers will become increasingly important to commercial businesses and, therefore, how retail and F&B premises accommodate them should be considered as part of the public realm building interface.

While there is a growing understanding of good practice in terms of cycle provision in the public realm, the provision of storage and parking facilities, particularly within homes (where most journeys begin), is still lagging.

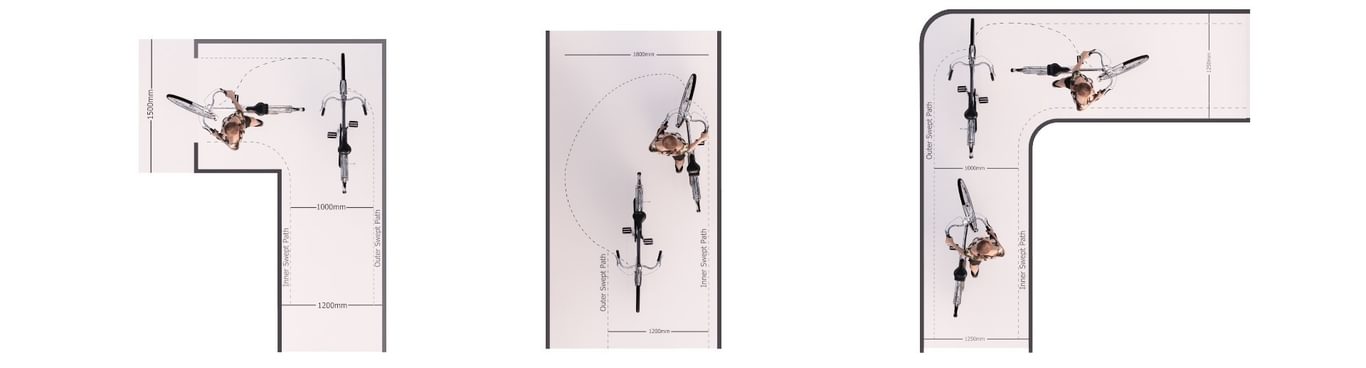

Having somewhere convenient and secure to store their cycles is an important issue for cyclists. In addition, entrances to all building types should accommodate the free movement of cyclists and their bikes, whether this is a dedicated cycle entrance or a common one.

Inside, sensible space planning will avoid the frustration of bike tangles.

We need to provide adequate, well-considered space and parking close to entrances that provides capacity without disrupting pedestrian flows and safety.

Domestic deliveries increased by 23% in 2020[iii], fuelled by the COVID-19 lockdown, with online food deliveries increasing by over 13%. This trend has seen significant growth in “last mile” distribution network delivery facilities and a consequent increase in small commercial vehicle movements and companies seeking alternative solutions for deliveries, including fixed-location lockers, cycles, drones, droids and autonomous ground vehicles (AGVs) with lockers. For a time, we will need to accommodate deliveries and fixed-location lockers in the urban realm while, in the future, rooftop pads for drones may be commonplace.

Commercial premises require daily refuse collections, whereas residential uses may be as infrequent as bi-weekly. In addition, food waste from restaurants needs to be processed differently to that from domestic premises.

All the differences do however have solutions and possible advantages if they are designed for cleverly. The proliferation of domestic wheelie bins has created logistical and aesthetic struggles in our urban streets. Equally, residents don’t want to have to step over piles of refuse bags put out by shops and cafés to get to their front doors. Designing in aggregating facilities will not only manage these issues but will also increase the potential for recycling and economies of collection.

These facilities may need management, if self- or community-management is not sufficient, and they may not be quite as convenient as putting the refuse outside the front door, but this form of neighbourhood facility operates well in other European cities.

[i] Jacobs, J. (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities

[ii] Louis Kahn, The Street

[iii] https://www.insightdiy.co.uk/n...

Is there anything to add to this? It is quite short.

Sentence deleted because it repeats what was said three paragraphs earlier.

This being repeat text from the previous paper, is it necessary to include?

Inside, sensible space planning will avoid the frustration of bike tangles.

INSERT STORAGE IMAGE

As previously commented some commercial premises, such as “grab and go” coffee shops, are already having to accommodate cyclists within their premises, as cyclists do not want to take the time to lock up their bike, even if the opportunity exists, while they grab their coffee.

We need to provide adequate, well-considered space and parking close to entrances that provides capacity without disrupting pedestrian flows and safety.

Servicing

Different uses have different servicing needs. While a resident may receive one or two deliveries a week, a shop or office may have daily or multiple deliveries. That being said, it is easier for the latter to set up schedules than for the former.

Businesses can significantly reduce the number of deliveries they receive by procuring their goods more efficiently in fewer, larger orders. Even greater benefits can be achieved when groups of businesses work together to jointly procure goods and services or to form “buying clubs”. Policies can also be agreed to prioritise electric vehicle deliveries.

Domestic deliveries increased by 23% in 2020 , fuelled by the COVID-19 lockdown, with online food deliveries increasing by over 13%. This trend has seen significant growth in “last mile” distribution network delivery facilities and a consequent increase in small commercial vehicle movements and companies seeking alternative solutions for deliveries, including fixed-location lockers, cycles, drones, droids and autonomous ground vehicles (AGVs) with lockers. For a time, we will need to accommodate deliveries and fixed-location lockers in the urban realm while, in the future, rooftop pads for drones may be commonplace.

Commercial premises require daily refuse collections, whereas residential uses may be as infrequent as bi-weekly. In addition, food waste from restaurants needs to be processed differently to that from domestic premises.

All the differences do however have solutions and possible advantages if they are designed for cleverly. The proliferation of domestic wheelie bins has created logistical and aesthetic struggles in our urban streets. Equally, residents don’t want to have to step over piles of refuse bags put out by shops and cafés to get to their front doors. Designing in aggregating facilities will not only manage these issues but will also increase the potential for recycling and economies of collection.

These facilities may need management, if self- or community-management is not sufficient, and they may not be quite as convenient as putting the refuse outside the front door, but this form of neighbourhood facility operates well in other European cities.

Jacobs, J. (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities