The evolution of Transport-Orientated Developments in China

Chapman Taylor has considerable worldwide experience of designing transport-orientated developments (TODs), from smaller bus or railway stations and their immediate environments to large, multi-modal interchanges and the entire urban districts around them. In China, we have tended to work on complex, large-scale TOD developments within wider urban masterplans, although we have also designed mixed-use developments with transport functions integrated within them. In this paper, Shanghai studio Associate Director Yichun Xu explains the latest approaches to Chinese TOD design, the complexities involved and why Chapman Taylor is well-placed to help deliver the next generation of TOD developments across China’s rapidly expanding towns and cities.

How has TOD design changed in China over recent years?

Whereas transport interchanges may once have been considered as separate, standalone buildings within a town or city, in recent years there has been an increasing emphasis on the important social and economic focal points that these hubs provide. Modern transport-orientated developments (TODs) aim to weave the transport function within a mix of other uses while integrating the design seamlessly with the surrounding context.

Until a few years ago, transport hub design in China was really just about moving people as efficiently as possible. These developments are now viewed as important destinations in their own right, with much more emphasis on townscape quality. A station is a key community asset, and its design should respond to this by reflecting local character and heritage, supporting integrated, cross-modal transport and considering the provision of open space amenity.

What does the latest TOD thinking involve?

In China, the latest approach to TOD design is described as “fourth generation”, integrating the station, the city and the people (where “third generation” TOD design tended only to emphasise station and city). The experience of passengers and visitors is a crucial element of successful TOD design, particularly in terms of providing an enjoyable and low-stress environment which is functionally fluid while encouraging people to dwell.

TOD design therefore covers not just the station and its immediate surroundings, but also the wider area, and can include a mix of residential, retail, leisure, office, civic and other uses with attractive public realm space to ensure that the whole area is vibrant throughout the day and late into the evening. The end result should be an urban space which is high energy, high density and with high connectivity.

The Kings Cross regeneration in London is a superb example of a successful TOD development, generating social and economic opportunities within an attractive mixed-use destination anchored by busy railway stations. What once felt like a somewhat unsafe and seedy urban environment has been transformed into a successful place to work, shop and socialize. Hong Kong is also an exemplar for efficient TOD design, with superb social infrastructure developed in a cohesive and intelligent way around its transport functions.

In China, cities are very densely developed and have large populations, requiring services and amenities to be squeezed into relatively small spaces. It therefore makes sense to make full use of the available opportunities to combine a mix of functions within strategically important urban transport developments.

What TODs has Chapman Taylor been working on?

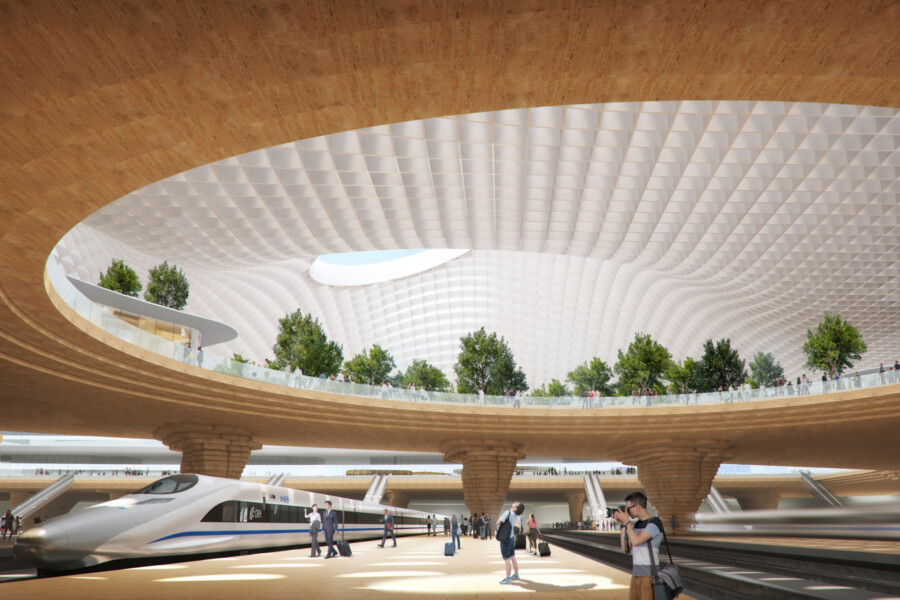

Most of the TOD projects which Chapman Taylor has designed in China involve new transport interchanges. As an example, for the 189-hectare Xili Hub Area in Shenzhen, we created a masterplan concept creating an innovative, efficient and attractive urban district as one of the city’s three key master hubs, integrating a new high-speed railway station within the district and the wider city.

The concept includes a sustainable railway and bus interchange complemented by a range of commercial and social amenities. Seven high-speed rail lines, three metro lines and several bus terminals are served by the development. A landscaped green corridor extends to each side of the station to blend with the natural landscape of the Xili area and the wider Nanshan district, while landscaping also softens what was a rigid urban road system around the site, helping to create a more attractive and welcoming urban environment.

The area’s upgraded road network increases traffic capacity and maximises accessibility. The new road system creates optimal north-south and east-west connections, helping to solve longstanding road congestion problems in the area. In terms of pedestrian and cycle traffic, beautifully landscaped paths and corridors connect the two urban cores around the site to the new hub area, serving to ensure the area’s full integration with the wider community.

Most major urban masterplans we create in China have a TOD at their core or are well connected to one. It is vital to consider how the various elements interconnect with the transportation function, how the landscaping strategy plays a role and many other aspects. In the past year, we have worked on three major TOD designs, including one which includes a high-speed railway station. There are many challenges involved, including circulation and functional efficiency, as well as detailed research and analysis to ensure that the functions and layout are appropriate for that location.

TOD design also plays a central role in brownfield, mixed-use developments. At Shanghai Global Harbor, for example, the development is served by three metro lines, one of which was added during construction, and two bus stations. Similarly, Lanzhou Global Harbor will create a mixed-use city centre development facing Lanzhou West mainline railway station. The development will include a retail and leisure destination, two 350-metre-high landmark towers, an office building the west side of the scheme and apartment buildings of varying heights to the east – all combining with beautifully landscaped urban spaces around the development to create a welcoming gateway to the city from the high-speed railway station.

A lot of new railway and metro stations are being built in new city districts away from the old city centres, so TOD-focused suburban town centres are a very prominent part of the growth of China’s cities.

What are some of the key elements of a successful TOD design?

The multi-level design is very important; transport hubs can carry tens of thousands of passengers each day, so the movements of these people through the spaces and levels has to be a central focus of the planning. In China, “vertical cities” are at the heart of urban design – arranging transport infrastructure vertically on several levels.

When we masterplanned the Xili Hub Area, for example, we carefully assessed at which levels the various transport lines, such as railway, buses, metro, pedestrian and cars should be located. We considered placing the railway station and the subway on the underground level so that passenger connections would be quicker and circulation more fluid, allowing for faster clearance.

However, we wanted the waiting areas above ground level to allow abundant natural light to reach them, one of a number of ingredients that help reduce passenger stress and improve wellbeing. We therefore positioned the station above ground level. Once that sectional structure was established, we had the framework within which the architecture, landscaping and other elements could be determined.

How do you create a good relationship between the transportation function and the wider area?

Most of our TOD projects are elements within wider urban masterplans. For these, the designs tend to be less architecturally ambitious than, for example, our design for Xili, but full integration with the surrounding area and architectural harmony with the context are just as essential. We design these projects on a human scale, creating spaces in which people can feel relaxed.

Increasingly, in China, there is a focus on concentric “living circles” in urban design, with, for example, a radius of 15 minutes’ walking time from a residential area containing everything that people living there need for daily life, or a radius of 30 minutes’ walk containing what is needed for monthly life, etc.

We have adopted this approach on some of our TOD masterplans, but with five-minute intervals instead, providing local community amenities within that first five minutes’ walk, and more city-level amenities and functions after 15-minutes. Each five-minute interval would be focused on appropriate forms of transport; for example, bicycles and walking at five minutes, buses at ten minutes, subway stations at 15 minutes. This, we believe, helps to create a more balanced, mixed-use district which serves people’s needs more effectively.

Can TOD design help the environment?

The more efficiently that people move around a town or city, the smaller the resulting carbon footprint. Well-considered TOD design should ensure fluidity and convenience, so that there is less need to use cars and a higher likelihood that people will use public transport. The best TOD designs streamline how that district operates to such an extent that the district is effectively carbon neutral.

Landscaping is another means of ensuring environmental sustainability, providing abundant greenery and creating spaces in which it is enjoyable to walk or cycle. When combined with “Sponge City” techniques (see our Insight paper on Sponge City design published on 26 August 2020), TOD landscaping strategies can help balance the environment to smooth out peaks and troughs in water supply while reducing pollution drastically, providing natural energy generation and increasing the district’s ability to capture and store carbon.

Adaptability is an important aspect of any project’s lifecycle sustainability and transport environments are no exception. The architecture of a station should take account of potential future needs, social changes, advances in technology and the evolution of modes of transport. The principal structures tend to be relatively unchanging, but secondary layers should be able to adapt within this relatively rigid shell to meet changes in flow, use, capacity and demand. The primary elements of transport hubs tend to be constructed to meet the capacity demand of the masterplan horizon, which may be 30 to 50 years. The role of the secondary layer, within that shell, is to provide a solution that can flex more frequently, according to demand.

Where next for TOD design?

In Japan, Toyota is working with designers and others to develop TOD design a stage further, looking beyond the era of widespread car use to concentrate on what they call “the last kilometre home” – the journey between the TOD and the passenger’s front door. This will draw in elements of Smart City design with, for example, real-time information on trains and buses being available in people’s homes. Chapman Taylor’s experience in Smart City design places us in a great position to be at the forefront of such a development in TOD design.

In China, we are also witnessing the beginning of a conversation about PODs – pedestrian-orientated developments – and the fourth generation of TODs is part of that. Pedestrian experience is an important consideration for the design of a successful and sustainable TOD, so there is an overlap with the aims of these new PODs. What this illustrates is that the days of concentrating just on functionality and adding in a little commerce are now over – TOD design has to be a lot more holistic in approach and sophisticated in execution.

What makes Chapman Taylor stand out among TOD designers?

Chapman Taylor always designs TODs with their specific contexts in mind, never approaching their design with preconceptions or templates. What works well for one place could be a disaster for another, so it is always crucial to start each project with a blank page and to research extensively before beginning to sketch ideas. At Xili, for example, the best design solution involved an above-ground, “floating” railway station, whereas in our masterplan for another major city’s inter-city railway station and TOD, we decided upon an underground, “invisible” station, because the context was very different.

The geography, history, culture, surrounding architecture, existing infrastructure, limitations and many other contextual features should be fundamental influences for any well-considered TOD design. It would be a disservice to clients and to the development’s end-users to approach TODs, or indeed any urban development project, in any other way.

TODs are also much more complex than “ordinary” mixed-use schemes; there are numerous additional complications and challenges, from safety and security to the need to deal with multiple stakeholders and authorities. Chapman Taylor has extensive worldwide experience of managing very complex, large-scale projects which involve careful and diplomatic liaison with clients, developers, multiple landowners, local and national authorities, railway, metro and bus operators, safety bodies and others from very early project stages. Our collaborative approach and problem-solving expertise lend themselves well to achieving successful outcomes.

Among China-based designers, we are distinguished by our focus on creating memorable townscapes with user experience in mind. Our ability to view a design, even from an early stage, from the point of view of an end user, whether that be a passenger, a pedestrian, a worker or a resident, is particularly valuable in terms of anticipating potential problems and solving them early. This approach lends itself well to creating innovative and dynamic places which create a strong sense of place and identity, optimise circulation and provide human-scale, enjoyable spaces while ensuring that the transport and other functions are efficient and future-proofed.

Stations are much more than just passenger interchanges with necessary commercial and passenger facilities. They are social hubs, integrated with, and providing for, a wider urban context. Chapman Taylor’s expertise in mixed-use urban masterplanning means that our team knows how to develop a TOD scheme that fulfils all of the necessary operational requirements while creating a successfully integrated urban development.

What does the latest TOD thinking involve?

In China, the latest approach to TOD design is described as “fourth generation”, integrating the station, the city and the people (where “third generation” TOD design tended only to emphasise station and city). The experience of passengers and visitors is a crucial element of successful TOD design, particularly in terms of providing an enjoyable and low-stress environment which is functionally fluid while encouraging people to dwell.

TOD design therefore covers not just the station and its immediate surroundings, but also the wider area, and can include a mix of residential, retail, leisure, office, civic and other uses with attractive public realm space to ensure that the whole area is vibrant throughout the day and late into the evening. The end result should be an urban space which is high energy, high density and with high connectivity.

The Kings Cross regeneration in London is a superb example of a successful TOD development, generating social and economic opportunities within an attractive mixed-use destination anchored by busy railway stations. What once felt like a somewhat unsafe and seedy urban environment has been transformed into a successful place to work, shop and socialize. Hong Kong is also an exemplar for efficient TOD design, with superb social infrastructure developed in a cohesive and intelligent way around its transport functions.

In China, cities are very densely developed and have large populations, requiring services and amenities to be squeezed into relatively small spaces. It therefore makes sense to make full use of the available opportunities to combine a mix of functions within strategically important urban transport developments.

What TODs has Chapman Taylor been working on?

Most of the TOD projects which Chapman Taylor has designed in China involve new transport interchanges. As an example, for the 189-hectare Xili Hub Area in Shenzhen, we created a masterplan concept creating an innovative, efficient and attractive urban district as one of the city’s three key master hubs, integrating a new high-speed railway station within the district and the wider city.

The concept includes a sustainable railway and bus interchange complemented by a range of commercial and social amenities. Seven high-speed rail lines, three metro lines and several bus terminals are served by the development. A landscaped green corridor extends to each side of the station to blend with the natural landscape of the Xili area and the wider Nanshan district, while landscaping also softens what was a rigid urban road system around the site, helping to create a more attractive and welcoming urban environment.

The area’s upgraded road network increases traffic capacity and maximises accessibility. The new road system creates optimal north-south and east-west connections, helping to solve longstanding road congestion problems in the area. In terms of pedestrian and cycle traffic, beautifully landscaped paths and corridors connect the two urban cores around the site to the new hub area, serving to ensure the area’s full integration with the wider community.

Most major urban masterplans we create in China have a TOD at their core or are well connected to one. It is vital to consider how the various elements interconnect with the transportation function, how the landscaping strategy plays a role and many other aspects. In the past year, we have worked on three major TOD designs, including one which includes a high-speed railway station. There are many challenges involved, including circulation and functional efficiency, as well as detailed research and analysis to ensure that the functions and layout are appropriate for that location.

TOD design also plays a central role in brownfield, mixed-use developments. At Shanghai Global Harbor, for example, the development is served by three metro lines, one of which was added during construction, and two bus stations. Similarly, Lanzhou Global Harbor will create a mixed-use city centre development facing Lanzhou West mainline railway station. The development will include a retail and leisure destination, two 350-metre-high landmark towers, an office building the west side of the scheme and apartment buildings of varying heights to the east – all combining with beautifully landscaped urban spaces around the development to create a welcoming gateway to the city from the high-speed railway station.

A lot of new railway and metro stations are being built in new city districts away from the old city centres, so TOD-focused suburban town centres are a very prominent part of the growth of China’s cities.

What are some of the key elements of a successful TOD design?

The multi-level design is very important; transport hubs can carry tens of thousands of passengers each day, so the movements of these people through the spaces and levels has to be a central focus of the planning. In China, “vertical cities” are at the heart of urban design – arranging transport infrastructure vertically on several levels.

When we masterplanned the Xili Hub Area, for example, we carefully assessed at which levels the various transport lines, such as railway, buses, metro, pedestrian and cars should be located. We considered placing the railway station and the subway on the underground level so that passenger connections would be quicker and circulation more fluid, allowing for faster clearance.

However, we wanted the waiting areas above ground level to allow abundant natural light to reach them, one of a number of ingredients that help reduce passenger stress and improve wellbeing. We therefore positioned the station above ground level. Once that sectional structure was established, we had the framework within which the architecture, landscaping and other elements could be determined.

How do you create a good relationship between the transportation function and the wider area?

Most of our TOD projects are elements within wider urban masterplans. For these, the designs tend to be less architecturally ambitious than, for example, our design for Xili, but full integration with the surrounding area and architectural harmony with the context are just as essential. We design these projects on a human scale, creating spaces in which people can feel relaxed.

Increasingly, in China, there is a focus on concentric “living circles” in urban design, with, for example, a radius of 15 minutes’ walking time from a residential area containing everything that people living there need for daily life, or a radius of 30 minutes’ walk containing what is needed for monthly life, etc.

We have adopted this approach on some of our TOD masterplans, but with five-minute intervals instead, providing local community amenities within that first five minutes’ walk, and more city-level amenities and functions after 15-minutes. Each five-minute interval would be focused on appropriate forms of transport; for example, bicycles and walking at five minutes, buses at ten minutes, subway stations at 15 minutes. This, we believe, helps to create a more balanced, mixed-use district which serves people’s needs more effectively.

Can TOD design help the environment?

The more efficiently that people move around a town or city, the smaller the resulting carbon footprint. Well-considered TOD design should ensure fluidity and convenience, so that there is less need to use cars and a higher likelihood that people will use public transport. The best TOD designs streamline how that district operates to such an extent that the district is effectively carbon neutral.

Landscaping is another means of ensuring environmental sustainability, providing abundant greenery and creating spaces in which it is enjoyable to walk or cycle. When combined with “Sponge City” techniques (see our Insight paper on Sponge City design published on August 2020), TOD landscaping strategies can help balance the environment to smooth out peaks and troughs in water supply while reducing pollution drastically, providing natural energy generation and increasing the district’s ability to capture and store carbon.

Adaptability is an important aspect of any project’s lifecycle sustainability and transport environments are no exception. The architecture of a station should take account of potential future needs, social changes, advances in technology and the evolution of modes of transport. The principal structures tend to be relatively unchanging, but secondary layers should be able to adapt within this relatively rigid shell to meet changes in flow, use, capacity and demand. The primary elements of transport hubs tend to be constructed to meet the capacity demand of the masterplan horizon, which may be 30 to 50 years. The role of the secondary layer, within that shell, is to provide a solution that can flex more frequently, according to demand.

Where next for TOD design?

In Japan, Toyota is working with designers and others to develop TOD design a stage further, looking beyond the era of widespread car use to concentrate on what they call “the last kilometre home” – the journey between the TOD and the passenger’s front door. This will draw in elements of Smart City design with, for example, real-time information on trains and buses being available in people’s homes. Chapman Taylor’s experience in Smart City design places us in a great position to be at the forefront of such a development in TOD design.

In China, we are also witnessing the beginning of a conversation about PODs – pedestrian-orientated developments – and the fourth generation of TODs is part of that. Pedestrian experience is an important consideration for the design of a successful and sustainable TOD, so there is an overlap with the aims of these new PODs. What this illustrates is that the days of concentrating just on functionality and adding in a little commerce are now over – TOD design has to be a lot more holistic in approach and sophisticated in execution.

What makes Chapman Taylor stand out among TOD designers?

Chapman Taylor always designs TODs with their specific contexts in mind, never approaching their design with preconceptions or templates. What works well for one place could be a disaster for another, so it is always crucial to start each project with a blank page and to research extensively before beginning to sketch ideas. At Xili, for example, the best design solution involved an above-ground, “floating” railway station, whereas in our masterplan for another major city’s inter-city railway station and TOD, we decided upon an underground, “invisible” station, because the context was very different.

The geography, history, culture, surrounding architecture, existing infrastructure, limitations and many other contextual features should be fundamental influences for any well-considered TOD design. It would be a disservice to clients and to the development’s end-users to approach TODs, or indeed any urban development project, in any other way.

TODs are also much more complex than “ordinary” mixed-use schemes; there are numerous additional complications and challenges, from safety and security to the need to deal with multiple stakeholders and authorities. Chapman Taylor has extensive worldwide experience of managing very complex, large-scale projects which involve careful and diplomatic liaison with clients, developers, multiple landowners, local and national authorities, railway, metro and bus operators, safety bodies and others from very early project stages. Our collaborative approach and problem-solving expertise lend themselves well to achieving successful outcomes.

Among China-based designers, we are distinguished by our focus on creating memorable townscapes with user experience in mind. Our ability to view a design, even from an early stage, from the point of view of an end user, whether that be a passenger, a pedestrian, a worker or a resident, is particularly valuable in terms of anticipating potential problems and solving them early. This approach lends itself well to creating innovative and dynamic places which create a strong sense of place and identity, optimise circulation and provide human-scale, enjoyable spaces while ensuring that the transport and other functions are efficient and future-proofed.

Stations are much more than just passenger interchanges with necessary commercial and passenger facilities. They are social hubs, integrated with, and providing for, a wider urban context. Chapman Taylor’s expertise in mixed-use urban masterplanning means that our team knows how to develop a TOD scheme that fulfils all of the necessary operational requirements while creating a successfully integrated urban development.